Photo: Permission provided by Kevin MacKay

Photo: Permission provided by Kevin MacKay

In this important new book from Between the Lines Press, Kevin MacKay clears a path through today’s social and ecological crises with sharp critique. Along the way, he rethinks causes, charts an alternative route, and guides us “toward a system of life.”

Kevin is a social science professor, union activist, and executive director of a community development cooperative. He lives in Hamilton, Ontario, and when not thinking, reading or writing about social change, can most likely be found in the woods.

Aurora: Hi Kevin, I really enjoyed your public talk about your book Radical Transformation. Today for the Aurora, we want to give the online readers a sense of what this book’s about, why you wrote it and hopefully we can dig in a couple of places.

![[cover] Radical Transformation by Kevin MacKay](1210/96-Image-1210-1-17-20171011.jpg)

Kevin MacKay: That would be wonderful.

Aurora: “Why this book and why now?”

Kevin MacKay: That’s a great place to start. I think for me it was an organic process of being involved in different movements over a number of years. So, when I say “different movements,” this includes environmental, social justice, the labour movement, etc. And over time, I slowly came to a realization that the crises that I was dealing with in these different areas - for instance in Hamilton the battle for the Red Hill Valley, which was an over 50-year conservation battle to save a natural river valley from expressway development - the kinds of issues I was encountering there were similar to the ones that I was encountering when I’d also be marching against the latest war that was being launched, or dealing with issues of economic justice through labour organizing.

The book emerged from a growing sense that these things were connected, and that what can seem like a bunch of individual fires being set were actually being set by one, not an individual in this case, but I would argue by a certain political and economic system. And so over time, I started to get more and more interested in the underlying structural condition that’s leading to these multiple crises in different areas. That led me to systems thinking, but really my original philosophical grounding was in the critical, post-Marxist tradition.

I started to see a productive place to merge these two ways of looking at the world. The goal was to try to understand just what was going on with an industrial capitalist civilization that, I started to realize, was in a terminal state of crisis. I think that this realization is not new.

Aurora: That sounds familiar.

Kevin MacKay: I’m definitely not the first person to say this, and in a way, I was writing in reaction to a number of thinkers who were starting to talk about our situation in quite dire terms. Not just that, “Oh maybe in a generation or two we’re going to be in trouble,” but people were starting to say, “You know, look, a collapse of industrial capitalism is not only possible, but maybe imminent.”

Aurora: Well there is a chorus of collapse and crisis singers out there right now.

Kevin MacKay: There is definitely a tradition that I mention in my book. Folks like Derrick Jensen, for instance, who wrote End Game and Deep Green Resistance.

Aurora: I missed those.

Kevin MacKay: Jared Diamond writes Collapse back in 2005, which is another example of these Apocalyptic narratives that are being put out there. I was really writing in reaction to this trend, and in particular to the fact that some of it was very nihilistic. I would put the Jensenite camp and John Zerzan in that nihilistic space.

Aurora: Who is Zerzan? I’ve heard of the name.

Kevin MacKay: He is thought of as one of the founders of Anarcho-primitivism.

Aurora: Oh! What can you tell us about that?

Kevin MacKay: So, their whole idea is just, “Let it all collapse,” you know, and supposedly there will be this glorious purification through population crash, and violence, and societal breakdown. And for many reasons, I just didn’t think that was a productive way to think about things. My unease with the “collapse is inevitable, collapse is good” prompted me to do the research and then write a book asking: “What is the crisis? How did it develop? How can we avert it?”

Aurora: Right. You posed the questions in a different way at your public talk. You asked, “Is it in our human nature to destroy ourselves?”

You flipped the issue around for the reader. Not how do we get out of collapse, but how do we get out of the trap of this collapse-ism literature?

A number of people at the book launch praised how you are trying to look for a positive, less nihilistic, way forward. In addition, your book does a lot of that work for readers.

Kevin MacKay: Well, I really appreciate the fact that a) you’ve read it, and b) that there were some things in it that were of interest to you.

Aurora: To set the context, you start with these five drivers of crisis, that you name the five horsemen of the Apocalypse.

And here, I thought you did unique things with each one that I hadn’t seen people do before, and the five are: dissociation, scale/complexity, stratification, overshoot and oligarchy, right?

Kevin MacKay: Yes.

Aurora: Let’s talk about dissociation. You identify three types - spatial, temporal and empathic.

Kevin MacKay: For sure. So, I think the interesting thing about past scholarship on the collapse of complex civilizations, is that it has taken the perspective of civilizations as problem solving, decision-making organizations.

Kevin MacKay: This theme goes back to Joseph Tainter’s book in 1998, The Collapse of Complex Societies, and Jared Diamond picks up on it again in 2005. Thomas Homer-Dixon echoes the theme in The Upside of Down, published in 2006. These are three important works that I’m drawing on in my own book. I think looking at societies as decision-making organizations is a very interesting perspective, and in ways it’s really productive. It also has weaknesses, which I can address later. However, the concept of dissociation flows from this idea of decision-making. If you can think of a civilization as a complex, adaptive system that constantly meets existential threats, challenges to its survival, then the civilization either decides to make the right decisions in the face of that threat, or it doesn’t.

Aurora: How does this help us?

Kevin MacKay: I think what’s useful about this way of thinking is that, it takes us away from some sort of environmental determinism and really throws us back to culture as being the most important variable that determines success or failure in the face of existential threat. Basically, you get this idea of “Can we make the right decisions?”

What dissociation speaks to is the difficulty of us making the right decisions in a society that is massive in scale, and in which we don’t get feedback about the impacts of our actions. In the book, I talk about three different ways in which that feedback loop between action and consequence is severed. Spatial displacement starts with the fact that we’re living right now in Canada, among the wealthiest countries in the world, and if you look at ecological footprint statistics, we’re maxing out our use of ecosystem resources.

Aurora: Yes. Ecological Footprint analysis has been a helpful tool for raising awareness. See the discussion in Aurora: William Rees, 2000.

Kevin MacKay: And a lot of Canadians, I would say most Canadians, have no concept of how our lifestyle, our high level of consumption or high level of waste, our high level of energy use, are negatively affecting communities in other parts of the globe. The reason is partly understandable. We just don’t see it, we don’t hear it, we don’t encounter it. Spatial displacement is simply that. Like I say in the book, most people don’t know where their food comes from. They don’t know where their waste goes to. They don’t know where their electricity comes from. You know, all of these things appear very abstract.

Aurora: Ok. I think our readers can identify with that.

Kevin MacKay: And because of this, it’s really hard to make correct decisions when one of the normal ways in which human beings rationally and cognitively navigate the world is by trying something and then seeing, “Oh wow, that’s what happened. That worked, or it didn’t work.” So, in a globalized, industrial civilization, we can’t get that feedback as easily, and that’s because of spatial displacement.

Aurora: How about temporal displacement?

Kevin MacKay: Temporal displacement is another challenge we face. A lot of the behaviours we’re engaging in as an industrial society have consequences that aren’t felt for 10, 20, 30, 40 years down the road. Examples of this include an industrial economy which is clear-cutting forests to sustain paper consumption, or it is overexploiting fish stocks to supply consumer markets. Or, it is rapidly extracting all the fossil fuels. And of course, what any ecologist will tell you is, “Over time, you simply can’t keep doing that.”

Kevin MacKay: In terms of the feedback between behaviour and consequence, the impact of industrial capitalism is thus catastrophic, but the problem is that the consequence comes far enough in the future that we are dissociated from it. We think “Well that’s down the road, right?” So, one form of dissociation occurs when a consequence is not an immediate temporal concern.

I also introduce a second way that time differs in a globalized economy. This is where I draw on David Harvey’s work on the compression of time and space that happens in industrial capitalism. Due to the need to constantly speed up the turnover of capital, Harvey argues that industrial society starts thinking of time in a very compressed sense. We start to see time scales get shorter and shorter in terms of how we think about cause and effect. This can be seen when looking at corporate time – based on financial quarters or year-ends, or the hyper compression of time that you see in the finance economy, where millions are won or lost in securities trading based on factions of a second.

Aurora: I recall some critics like Ian Angus Editor of Climate & Capitalism arguing that cycles of capitalism are changing outside of natural cycles nowadays, so rapidly cycling that natures’ cycles can’t accommodate them or their destructiveness.

Kevin MacKay: The last way in which we are cut off from the effects of our actions, empathic displacement, is related to the other two. It’s the idea that if we don’t see the impacts that our day to day actions are having on other human beings, then it’s difficult for us to engage the natural empathic feedback mechanism that we have, where we don’t want to cause harm to other human beings. We see this when the “others” are people living in marginal communities, maybe poor folks living in other parts of the world where we are exploiting their resources for our own use. We don’t see the effects of our actions on these people.

I think it has been established through research that most psychologically normal human beings don’t enjoy inflicting arbitrary harm on other people.

Aurora: I can see that empathic dissociation holds all the more for future generations, the impacts of our negative behaviour on them are distant from our western consciousness.

Kevin MacKay: And so, there’s that empathic capacity that we have which is wonderful, which historically helps us live in a community and helps us care for others. But if we don’t see the harm being done, if we’re not able to connect with it, then I think that’s a real problem. A concrete example is the need for oil by advanced industrial economies. For a number of years now this has led to a foreign policy based on violent control of those resources through warfare. Thus, we see the United States, Canada, and Western Europe oppressing, attacking, bombing, and controlling populations in the Middle East to access their oil reserves. And these actions are a horrendous crime. They’re making the lives of people in those regions absolutely miserable. Horrendous, but we don’t see it, and so we don’t connect with that suffering.

Aurora: Well I might argue even when we do see it, we still don’t connect with it negatively. Often, we see it as a necessary step in societal progress, to release the resource for the good of humanity. Also, we see things now that we didn’t see when I was younger. I remember in the late 60’s what helped change thinking about the war in Vietnam were news reports.

The ideological bullshit that was coming out of Washington was overridden completely by a two-minute clip of young North Americans dying, and we were the same age. And that changed young people’s and many parent’s politics and practice. But now there’s a kind of insensitivity almost. We see violence and war so much nightly on the news. I know in my own life I’ve reduced television to eliminate it from my life, but as I visit my friends or I visit my mom here - she wants to know every day what’s going on. CNN is on every day, all day. The same breaking news all day. I can see how you become desensitized to even death. If you look at the war in Syria daily.

Kevin MacKay: And then how it’s being framed, right?

Aurora: Yeah that is right, how ‘those people’ over there are being framed by the different powers.

Kevin MacKay: That’s a really important aspect, because I think that what truncates our natural empathic connection with other human beings is a combination of a few different things. One is space and time. But another is what I talk about in my book as “empathic boundary markers.” So, these are ways that we demarcate self from other. This comes from the idea that, yes, we’re social, but the downside of that is we can also be very tribal as human beings. So, those considered “us” we’re very tight and very close with. With those considered “other”, there is a bit of a disconnect to be breached. I think that the framing of news by corporate media [does not] help us to breach that empathic boundary. On the contrary, I think it builds it up in the sense of convincing us that the people getting killed by our bombs are “bad people”.

Aurora: I see your point. Michael Parenti has written much about this ‘othering’ process and the role of the media in it. Even my own example erased the suffering other. I stand corrected.

Kevin MacKay: Yes. They’re “terrorists” and they’re “other”. So, they’re dehumanized. And I think that’s part of the problem too.

Aurora: Before we move on, I would like to explore the topic of empathy a bit more. As I read the book, I really got excited that you recovered the empathic abilities of Western people. So often we only attribute empathy to others.

“Oh well, indigenous people have a seven generation empathic ability. And they can empathize with organic and inorganic nature,” but that’s not in our nature. Somehow we’ve come to, in western society to assume it’s not in our nature. What I found the strength in Radical Transformation was if we’re going to “chart a way forward” as you describe it, we need to recover our empathic nature, for which you and others provide a strong historical and anthropological record of evidence. We need to make it central again in our day to day politics, and recover what others have called a “moral economy.”

I hope readers enjoy this thread through your argument.

Now I want to turn to a few other concepts that you use in the book, in new ways. Do you mind if we just walk through the ideas of scale, and complexity and the others?

And then come back to the overall thesis about life systems and death systems.

Kevin MacKay: Definitely. So, I’ll give you a more condensed synopsis then.

Scale and complexity, this is the one where in the talk I gave at the book launch I joke that there’s two people riding one horse. It really should be six horsemen; however, scale and complexity are closely related. They address the fact that today we have a civilization that, I think for the first time, we can justifiably call a “global civilization.” This industrial capitalist mode of production has connected the entire planet, so if that’s a fundamentally flawed and dysfunctional mode of civilization, then it threatens the entire global political and economic system. The original heading for that chapter on scale and complexity was “Nowhere to Run, Nowhere to Hide.” It’s not just that one civilization is in big trouble and is going to collapse, and there will be a ripple effect, but everyone else is doing things better.

No, we’re all enmeshed in this system, and to me that’s where we can speak meaningfully of a real catastrophic global collapse if we keep going in this direction.

The complexity piece is that, because you’re talking about a global system, you’re talking about a profound level of complexity as well. This brings with it problems of being able to predict catastrophic tipping points, being able to predict instances of what systems theorists call “systemic risk”, as opposed to more localized risk.

A useful analogy is stock market crashes. You can talk about it in the context of the great depression, or more recently in 2007, 2008. There is risky behaviour being engaged in by a number of people in the high stakes finance market in the United States, Canada, in Europe - really all over the world. And that individual risky behaviour involves such things as falsely increasing the value of IPOs (initial public offerings) and building up housing bubbles in order to profit from them. All these things, there’s individual risk in the sense that if you’re an individual hedge fund manager, you may make money, you may not. But what people don’t realize is that if you scale that behaviour up, and its complex nature is connected globally, that it’s possible for localized risk to suddenly ripple out and become systemic risk and collapse the whole system.

Aurora: Yes. I have some American friends who were upside down on their mortgages.

Kevin MacKay: The problem is that it is hard to call when that is going to happen. Just like in any complex system, tipping points, in hindsight you say, “Oh that was a tipping point apparently”, but leading up to it.

Aurora: You don’t see it.

Kevin MacKay: Yeah. We’re seeing this with global climate change too.

So, with scale and complexity, it’s really an issue of, localized risky behaviour being one thing, but when you scale that behaviour up massively, you can crash the whole system, and that’s a huge problem.

Aurora: I liked how you used complexity in the book because probably older people (like me- Editor) will recall discussions about the El Nino effect or butterfly effect, and they get the connections in a complex system, but they haven’t connected those metaphors to how we could collapse a global ecosystem on which we all depend to live, Earth’s life systems.

Kevin MacKay: The biosphere, quite literally.

Aurora: The biosphere itself. The Gaia thinkers and others have drawn awareness to this, but I liked the way you’ve done it in the book. The way you used the five horsemen in combination brought my thinking to another level. So, can we move to the other three.

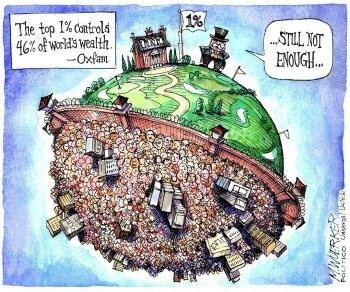

Kevin MacKay: For sure. So, stratification is the third horseman, and what’s interesting is research coming out recently that has started meaningfully incorporating stratification, which is just the technical term for talking about the gap between rich and poor.

They’re starting to meaningfully include that as a key variable predicting complex society collapse. One model is the HANDY Model: Human and Nature Dynamics. It was developed by a team of researchers who published a paper in Ecological Economics, and they’re using predictive computer models.

They’re playing simulations, setting up certain parameters for a civilization, then running the model. And what this Human and Nature Dynamics model was showing, which is quite interesting, is that obviously the degree to which a society is ecologically intensive is a huge variable for collapse, but equally important is the amount of income inequality in that society.

I think this conclusion is true for two reasons. One is that massive inequality usually correlates with high levels of people living in acute economic insecurity. That has a constant destabilizing influence on political and economic systems. And I think you see this in capitalism, and you see this even before capitalism, this constant cycle of economies becoming more and more unequal to the point that any sort of social cohesion or social contract breaks down. So, there’s a systemic problem there which is that it constantly undermines the viability of the decision-making organization. You simply can’t make decisions anymore.

But that’s a very technical problem with stratification. The moral problem of stratification is that you’ve got billions of people living in misery.

You have horrendous suffering, right from the colonial era through to the present day. One of the things in my book that I talk about is that there are natural system limits in the sense of, “Oh, this particular dysfunction is going to affect us all negatively,” but there’s also moral limits in the sense of, “What are we doing as a civilization?” Can we keep moving forward knowing that the ease of a very few, maybe 20% of the global population, is based on the misery of 50% of the global population? And to me that’s morally untenable. And so, that’s also what the problem of stratification speaks to.

(Image credit: M. Wuerker, Politico Universal Uclick.)

Aurora: When I read that argument, I was thinking of your own biography. Living in Hamilton through a period, really the de-industrialization period.

Kevin MacKay: Totally.

Aurora: Did that shape your thinking of all this somehow?

Kevin MacKay: It really did. I talk a bit about it in the book, experiencing not having any money myself, and experiencing poverty, living downtown, seeing that all around me, and experiencing that culture firsthand. But it was also realizing that, as tough as my experience was, it was nothing compared to what folks in other parts of the world face – countless people who literally didn’t get the chance to survive as long as I have.

I think in a weird way I’ve been lucky. I’m speaking as someone now who’s very privileged. I was lucky to experience poverty because it gives you a sense of some of the realities of being on the lower end of the socio-economic spectrum, the realities of how that really constrains your life experience, your life chances, and your life possibilities. And I learned too just how disconnected elite decision making systems are from the lived reality of the poor, or of people being racially discriminated against, or for whatever reason they’ve been marginalized or excluded.

As I say in the book, the standard elite narrative about poverty is people not working hard enough. And it’s just such complete bullshit if you’ve had any kind of taste of poverty.

Aurora: The next concept is overshoot and I would like to move you there.

Kevin MacKay: For sure. I think that it’s maybe one of the most, I would hope, obvious.

Aurora: I would hope so.

Kevin MacKay: Even so, I definitely do my best to go over some of civilization’s - I don’t want to call them highlights - more like low lights, ecologically speaking. At this point, the basic thesis of overshoot has been borne out. Every single branch of ecological science would affirm that all of the ecosystems we rely on for human survival are being critically degraded.

The concept of overshoot goes back to William Catton’s seminal book. Catton was the sociologist who pointed out the problem that if you have a population living on a land base, and the population’s consumption exceeds the ability of the land base to sustain them, then the population crashes. That’s just quite simple. We see it in nature over and over again. To think that we’re somehow immune from this dynamic is a total fantasy. And what’s interesting is that when Catton wrote the book; this was in the 80’s – he said, “We’re already in overshoot. This isn’t something we’re approaching.”

Aurora: I didn’t recall that. Thanks.

Kevin MacKay: And this is what’s interesting about the early writings of the environmental movement, whether it’s the Limits to Growth study the Club of Rome put out in the early 1970’s, or Rachel Carson writing in the late 1960’s. Already those people were very prescient, and they realized even then that we were in a period of overshoot. It’s gotten exponentially worse since then. I say in the book that in terms of the hardness of limits, those concerning ecology are the hardest. When the fresh water aquifers are finally drawn down, like the Ogalalla in the central United States, even though you can’t necessarily destroy fresh water, you can make it so that it’s going to take three to four thousand years for that aquifer to replenish through the normal hydrologic cycle. That’s a hard limit. And can you sustain a given population in the interim? Only at a fraction of the size. So yeah, it’s pretty serious.

Aurora: Bill Rees talked about ghost acreage, linking footprint to imperialism. He and others took it a little bit further and said, “Well okay, if you overuse what’s in your region, it’ll collapse, but imperial societies live on ghost acres. They draw in from other places that they control or have power over.”

Kevin MacKay: That is a fundamental contradiction of oligarchy. You’re exactly right, when we exhaust our own land base, we seize the land base of others.

(Source: popularresistance.org)

Aurora: We’re at oligarchy now, the last and most powerful horseman, so let’s talk a little bit about that.

Kevin MacKay: For sure.

Aurora: You take on Hobbes and the assumption that human nature is selfish, a war of all against all, and thus the need for a strong ruler, or Leviathan.

Kevin MacKay: Yes. I focus on oligarchy partly because I’m writing in the tradition of other thinkers who look at societies as decision making organizations. Given this frame, it’s natural to think about “How do we make decisions as a society?” I mean, it seems pretty important to factor in.

What was interesting to me was that a lot of systems thinkers tended to under theorize this aspect. They tended to downplay the real constraints on societal decision-making, and to me that weakness was conversely the great strength of the left critical tradition. To left thinkers, our society’s dysfunctions are because those people making decisions are doing so based on pursuing their own selfish interests. Beyond that, these people are able to then structure the entire social system to pursue their interests. All manner of catastrophic consequences come from this dynamic, which is why I call it not only the fifth horseman, but the one dysfunctional pattern that overarches the entire systemic pathology.

If we’re not able to make the decisions that we need to make, then we fail. We collapse. There’s just no other way around it, and there is an important point to be made here. If you look at all the different problems we’ve talked about: war, global warming, economic collapse. I would argue that in none of those instances is the problem technical. In none of them is the issue that we lack the knowledge, the experience, or the ability to make the required changes. We have all of that knowledge and capacity.

Kevin MacKay: Even if you think in terms of energy sustainability, fresh water, even the hard problems, we know what we need to do and we could do it. The real problem is just that, politically, the system is set up so that things that are very possible become impossible. To me that’s the real nexus of dysfunction. If we could change the way in which we’re able to make decisions, to make them collectively for the true benefit of the democratic community and the biosphere, then the crisis is very resolvable. But the current oligarchic system makes such a scenario impossible.

Aurora: When Graham MacQueen introduced you, I thought he paid you a great compliment, a true compliment about your book, and the way you write, making these very complex ideas accessible to everyday people.

Kevin MacKay: I hope so.

Aurora: And he had talked particularly about two additional narratives in your book: the life system and the death system. If we can go there for a while and maybe explain those to our readers and listeners and then we can come back to oligarchy a little bit and talk about making radical transformations. How does that sound?

Kevin MacKay: It sounds great. The discussion of oligarchy does feed into what, in the book, I call the “death system and the life system”. This is where my analysis reflects my own background as an anthropologist and someone who’s done a lot of reading in pre-history and archeology. I’m keenly interested in questions of origins.

To me, part of understanding the current crisis involves understanding its genesis and how it evolved and developed. I started by analyzing where we’re at right now. You have a numerically small, self-interested elite that structure social relations in their own interests. This is how I define it in chapter 6 of the book when I talk about oligarchy. At that point I go through, pretty exhaustively, all of the different ways that it manifests.

Chapter 6 is where I make the point that this condition is real and that our decision-making is, to an incredible extent, controlled by a very small group of people. From this point the next interesting question is, “How did that start?” Well, there’s one narrative about how it started. It’s a very powerful narrative, and it says, “Because that’s who we are. That’s who we are as human beings. We’re hierarchical. We’re aggressive. We’re competitive.”

Aurora: That’s the Hobbesian thesis, right?

Kevin MacKay: Exactly. The Hobbesian thesis is that a free expression of human nature leads to the war of all against all, and what keeps that from happening is the powerful sovereign, the authoritarian big brother, or “daddy” who keeps us in check. My take on this thesis is that, if you look at current research and at history, that it is actually a complete inversion of the truth. This is where, for me, Jean Jacques Rousseau had it right. In his Discourse on the Origins of Inequality Rousseau was saying, contrary to Hobbes, “No, that’s not it at all. It’s actually the introduction of the sovereign or the introduction of oligarchy that was the death blow to how we really interact as human beings.” And I think when you look at the evolution of the human species, it’s a very compelling narrative, and that Rousseau’s view is borne out. There’s no substantial debate today about the fact that homo sapiens sapiens evolved in egalitarian, democratic, and ecologically sustainable groups. If you’re going to talk about a human nature at all, I think you look at the first 180,000 years of our existence and you say, “Well, that’s how we lived.”

Aurora: On the basis of cooperation and other reciprocal values you mean?

Kevin MacKay: Yes. I think that’s a very important story to get out and I think it’s a narrative about who we are, where we started from, and then what went wrong. To me understanding “what went wrong” means understanding “How did we move away from these very cooperative, egalitarian societies?” I talk about these early human communities being based on the “primordial adaptive complex.”

Aurora: Yes. You had me there.

Kevin MacKay: Because part of the fun about writing a book is creating your own groovy terms.

Aurora: That was a great term.

Kevin MacKay: I tried to resist the urge to create new concepts, but that was an important one. I’m saying that if you’re going to define us in relation to other critters, then you have to talk about our immense intelligence and highly complex consciousness. The reason why that’s an important point is partly because a lot of people consider it to be obvious. We’ve got these massive craniums and incredibly complex cortex, but there are other intelligent animals out there. There are also other very cooperative animals like ants and bees and termites. However, the nature of our intelligence is that it’s creative, it’s individual, and it’s unique.

You get this interesting mix with human beings. We have an incredibly complex consciousness, which makes us unique, autonomous beings, and yet we express that in community and in cooperation. So, there’s this wonderful tension in human nature between what I call “creative intelligence”, which makes us individual, thinking persons, and the fact that we’re innately cooperative and empathic. We have the ability to experience the other as self. We have the ability to care for the other as self, and we have the incredible ability to expand this beyond human beings and towards the natural world. This is what a lot of traditional or indigenous cultures do. It’s wonderful, and it’s incredibly adaptive. If you think about it from an evolutionary perspective - no wonder we were able to survive.

Part of the story of early human evolution that’s quite interesting is that a number of researchers think we only narrowly survived. There were a number of other hominid groups that were alive at the same time as fully anatomically modern human beings. They didn’t make it because conditions were incredibly harsh in terms of climatic changes and masses of flora and fauna that were wiped out in short time periods during the Pleistocene. So how were we able to survive this harsh environment and to get through the eye of the needle? Research suggests it’s because we were smart, but also because we were highly cooperative and we had these cohesive social bands. And we had human culture, which only comes from intensive social interaction.

Aurora: So, you are being careful with the word innate, which sounds pre-social. But you are describing a socialization process of cooperation and creative adaptive capacity here.

Kevin MacKay: Yes. Human culture is the most powerful adaptive mechanism life on earth has ever produced. Humans can effectively create our sustainability wherever we want through tool use and through our collective problem solving abilities. I think it’s interesting that a lot of Hobbesians like to pretend that we’re more like tigers, we’re like the lone predators, you know, or like pan troglodytes as opposed to pan bonobo. They like to think that we’re these patriarchal, hierarchical, combative primates, but I think the weight of evidence is completely in the other direction.

So, we start out this way and then what happens? To me that was the interesting question from an evolutionary perspective. How did that initial highly adaptive, highly successful mode of being change? And there is a wonderful research literature on that question called “transegalitarian studies”. I’m working on a second book, and it dives much more deeply into that field.

Aurora: Oh really? Can you give us a glimpse?

Kevin MacKay: The second book is about human nature. It’s a more in-depth exploration of the narrative of human origins and the pre-historic transformation of human society.

Aurora: You know one thing that came to my mind, being another generation social scientist than you, was I started my career in a combined anthropology and sociology department and one of the great tragedies in some way has been the separation of the two. Even with critical thinkers, if you read the debate now about anthropocene and capitalocene, for many it starts with capitalism. They don’t want to go back further.

But if they had thought in the way that you are pressing them to say, “Well what about evolutionary biology? What does it teach us? What can we learn from early social anthropology? Or archaeology and collapse in Mayan boomtowns – which one of my colleagues is studying? Are there continuities and discontinuities and what do they teach us?”

Kevin MacKay: Totally.

Aurora: We’re so preoccupied I think as contemporary academics trying to think about transition that we don’t go back and read some of what you have read.

Kevin MacKay: I completely agree. As someone who’s studied anthropology, sociology, and psychology too, what really struck me was the productive ways in which those disciplines inform each other.

Aurora: I got a few things out of this book that actually helped me sort of get over some of my own academic biases.

Kevin MacKay: I’m sure I share some of them. I do think, and of course this is where there will be good criticism of my book, that each discipline also has its blind spots too. For instance, I think psychology has got some huge ones.

Aurora: You won’t get any disagreement from me on that one.

Now, you also draw on David Harvey’s work to discuss how there’s a new kind of speed to life nowadays. Time space compression does that, but there was another moment in history during the transition from feudalism to capitalism when ‘time’ also became the focus of social debate and social struggle.

Kevin MacKay: Very much so.

Aurora: And a certain oligarchy of capitalist factory owners and the state imposed their notion of time on the new working classes and the old peasant classes.

Kevin MacKay: Definitely. And their notion of productivity, their notion of the aims and goals of life. Everything becomes - in the book I actually say “twisted”, in terms of what a human life became. With the rise of oligarchy, it changed dramatically.

Aurora: I would like you to talk a bit more about that.

Kevin MacKay: Yes. So, a quick summary of the change would be that you have these small, highly adaptive bands that human beings exist in for 90% of our documented existence in the archeological record. Then what happens is these bands start becoming victims of their own success, in the sense that the survivability of humans increases. There is help ecologically speaking, as we enter into a period of relatively stable climate in which we’re able to thrive. But also, it’s the adaptive power of culture.

Through culture we start being able to contend with several different environments. We get better at procuring food, and certain things start happening. We become sedentary (and sedentary living comes before agriculture, actually in certain cases long before agriculture). Population starts growing. Now all of a sudden, you’re not a fluid, moving band, such that if another band comes in that you don’t get along with, you just move away. This increases the likelihood of conflict, but we’ve got to be careful here, because what a lot of Hobbesians forget is that if we’re living in a band that’s about 150 to 200 people, actually maybe 50 to 150 at times, then that’s not a viable breeding population. So, a lot of folks don’t understand that thinking each little band of early humans was in a hostile relationship to all other bands is completely absurd. The bands did meet regularly and exchanged partners.

I remember one evolutionary biologist, I took his course at McMaster years ago, he said, “When the bands would meet, it wasn’t often that they fight, but they’d nearly always breed” in the sense that it was much more likely that you would exchange knowledge, materials, and partners than it was that you would be in conflict.

That condition started to change when all of a sudden, if you’re sedentary, now you have land that you don’t want to move from. You have land that is now associated with value, you have an interest in controlling it, and a whole host of issues then arise. This is where I love the concept from archeology of an evolutionary ratchet. You get certain changes in social structure that become hard to move back from, and they have unintended consequences. I think the story of the emergence of oligarchy is, in the beginning, one of unintended consequences where suddenly you need increased levels of administrative hierarchy to deal with a population that is larger and more diverse.

Because you now have three or four bands that come together to live in a certain area, the simple, effective democratic structures that you can use when you’re in a band of 50 to 150 people don’t work anymore. So, you need higher levels of administration and you need more complex articulations of group identity that allow for different peoples to be a part of a larger body. So, you move from what we call a “band society” to a “tribal society”, and eventually to “chiefdoms”. At each stage, you have more levels of hierarchy - which in the beginning are still largely responsive to the group. At first, they haven’t become delinked from the democratic community. It isn’t until fully oligarchic societies - complex chiefdoms and archaic states - where you really have a political class that’s able to delink from the population in terms of their interests. They’re no longer a leadership that serves the people, but instead become a predatory leadership which lives off the people.

Aurora: Right.

Kevin MacKay: That’s where I would consider the change from the life system to the death system comes into play, because what happens then is all of a sudden you get societies which expand, which paradoxically seems to be a success at a certain point. Empires expand, and they’re fighting wars on all fronts, and you get into the early history of states. It seems like cultural progression and achievement, but they always collapse. Always.

Aurora: Sounds heroic for a while…

Kevin MacKay: Exactly. You see countless examples of monolithic architecture lionizing the kings of ancient empires: “During the reign of this ruler we fought back the hordes here and expanded boundaries here”. And you’re right, it all sounds very heroic and very successful. Yet the truth is that it always ends in collapse and constant warfare and constant misery. It also leads to the creation of a toiling underclass, and you start to see fascinating things. In the fossil record, you see bone density decreasing in human skeletons between when they were hunter-gatherers to when they made the switch to sedentary agriculture. Even physically, we see the toiling classes became less healthy.

Aurora: I have read different studies that confirm this.

Kevin MacKay: Whereas the elite classes start to completely delink in terms of their own material wealth.

Aurora: I was just in Europe and it’s amazing how many Roman aqueducts and ancient walls and amazing cathedrals there are, and I always think of Bertold Brecht’s great poem, “Who built the Great Wall of China?” You know because everybody talks about the great emperors are responsible for great works, but Brecht writes, “No, no, emperors didn’t do this. It was toiling classes” as you call them and I think the same. Who actually did this work? What was their life like? When you see fortified walls and castle-like buildings around a city as big as Toledo, in Spain, that are many metres tall and wide you go, “Who built all this?”

Kevin MacKay: Totally.

Aurora: Especially when you think about how hard it is to build a wall in your own garden by yourself.

Kevin MacKay: A little retaining wall or something.

And to me that speaks to the paradox of civilization as well. This is where I talk about the blending of the death system and life system. The paradox of civilization is that many of our past achievements are a testament to the collective creative potential of human beings. And so, you’re right when you look at the cathedrals, palaces, even the pyramids, and ask “Who built it? “Well that was built by Ramses.” No, it wasn’t. Like you said, it was built by thousands of workers, slaves, artisans, you name it, right? So, it’s only possible to do that, even the most ostentatious examples of oligarchic power are only possible, because they’re based on the life system. And that is democratic, collective, cooperative human behaviour.

With the emergence of oligarchy, it’s almost like that productive system, that adaptive system, gets “gamed”, or “hacked” by the elite. They’re then able to direct much of culture’s productive energy towards ends that are ultimately destructive and brutalizing of populations. It’s an act of deceit, of, as Rousseau’s termed it, “adroit usurpation”. It means taking that wonderful collective potential that we have and directing it towards building nuclear weapons and chemical weapons and whatever other monstrosities exist within the oligarchic imaginarium.

Aurora: You talk about hegemony later in the book and use some ideas from Gramsci and others and my favourite quote from Raymond Williams, actually one of the best descriptions of hegemony.

Kevin MacKay: Definitely.

Aurora: I find people don’t get it that hegemony or elite rule by consent has to be rebuilt and reconstituted constantly. The idea of constant struggle under hegemonic rule allows us to retrieve from your description of the death system and oligarchy, that within that there is resistance and there are some elements within the death system that people protected and have used to sustain themselves, whether it’s cooperation or types of democracy and some achievements.

You didn’t mention a thinker that I and many of my colleagues have been reading and are using, Karl Polanyi and his idea of Double Movement - that within these struggles there are pressures that Williams describes, there are pressures that are pushing back, right?

Kevin MacKay: Definitely.

Aurora: And so, a lot of people in the social economy or the peer to peer movement or some of these contemporary solidarity economy efforts to go beyond capitalism draw a lot on Polanyi. They say, “What we like about the Double Movement is that there are limits to hegemony”, right? And to maintain your inequity you need to condone a certain level of democratic achievement, such as the welfare state and the public sector that helps ordinary people, or the health care system and education systems you mention in your book. These achievements are actually won by popular struggles with elites within a stage of the hegemonic growth of capitalism. Hegemony creates contradictions and double movements that people can then perhaps exploit as at least pathways to articulate an alternative.

Kevin MacKay: Yeah. Definitely.

Aurora: I want to talk about the last part of the book that deals with radical transformation. Why did you choose the title, “Radical Transformation?

Kevin MacKay: It’s a great question, and I’m not sure it’s even the right title. It’s funny, a good friend and colleague of mine said, “It’s really good you included the secondary title, because if you just had the first title it would sound like a really bad self-help book.” Like, “If you can think it, you can be it! Radical Transformation!”

Joking aside, the word “radical” speaks to the fact that I hope the analysis I’m putting forward is dealing with root causes of dysfunction.

And that doesn’t just involve a radical analysis of what’s happening, which to me means just a more valid analysis. With radical analysis, you look beyond the surface phenomena. You’re trying to get the, “What’s really going on?”, but also to generate radical prescriptions for change. And by that I don’t mean in the popular sense of the word, which references actions that are highly confrontational, often alienating, self-righteous, and a little bit wacky at times. What I mean by radical change, is change that’s actually going to work.

Aurora: Tell me more.

Kevin MacKay: The idea of radical transformation is really thinking about, “Where do we truly want to go?” I spend some time talking about that in the last chapter, where I envision what I would call a “democratic, eco-socialist” state. This is a society where we can look around and say “We’re ecologically sustainable and all members of the human family are brought within the bounds of moral community”. To actually get there, to me, is radical.

And so, that’s where the term “radical” comes from. Transformation relates to the fact that I love the word “revolution”, but it’s a different thing, and I don’t want to mess with its specific, historical definition. I don’t want to muddy those waters, as while I am critical of revolution and insurrection, they are also things that I’m not ideologically opposed to. I think that they have their time and place. They do certain things well, they do other things not so well.

Aurora: And sometimes they happen but you don’t plan them.

Kevin MacKay: Exactly, and that’s part of the ebb and flow of social change. In North America, right now I don’t think we’re going to have a revolution any time soon. Some people could argue vociferously against that statement, and that’s fair enough.

Aurora: Well in your critique of this sort of activist approach, you make an interesting critique of reformism versus radical change towards what you call gradual radicalism. I like that concept and how you use the evolutionary ratchet as part of gradual radicalism. That’s what I see in it anyway.

Kevin MacKay: A hundred percent.

Aurora: Maybe we can talk about that, “How do we move from reformism to radical change then?”

Kevin MacKay: And the bigger question of, “How do you move from where we are now in a state of dysfunction and crisis, towards the world we want?”

I would call what we’re aiming for a “sane, humane, sustainable world”. One of the great debates when considering this question of moving from where we are to where we want to be is reformism versus radicalism. Do you go the rapid change, full monty, “get rid of all the elites tomorrow” route, or do you grind it out and win smaller, strategic victories? The risk of reformism is that you never get to where you want to go because hegemonic systems are sophisticated and they’re able to ground out reformist change. They’re able to roll with reformist strategies quite effectively and still maintain elite control.

Conversely, the risk of an ultra radical approach or an insurrectionary approach is that a lot of times they just don’t work. Understanding this failure is where, for me, Gramsci is so important. He argues that power in modern, industrial, capitalist states is hegemonic, which means it’s subtle and sophisticated, and that the power structure has a high degree of legitimacy in the eyes of most of the population. Even though people also don’t like it in a lot of ways, because I think the regular population is sophisticated too. I don’t think this is a straight false consciousness situation.

It’s more because over time (and this is where the evolutionary ratchet comes in), the life system, which is the democratic human community, has constantly pushed back against its exploitation by oligarchy. Constantly. And I think that is one of the things I appreciate about Bakunin and the Anarchist tradition. Bakunin talked about an innate propensity to rebel in human beings. I actually agree with that.

Aurora: My innate sociologist is quivering a bit, but I get it.

Kevin MacKay: For me, it is the innate attempt by human beings to reassert moral community, which is to create a world that operates under understandable and reasonable moral rules. I think that desire expresses itself as a propensity to rebel when moral community is constantly under attack, and when it’s being eroded.

We rebel when moral community is being twisted, and when instead of protecting and sustaining the people, it’s being used against them in really sinister ways. So, I think that we constantly try to reassert its pure form, and paradoxically, it’s that innate democratic drive in us that enables any kind of stability for oligarchic societies. If those societies were purely predatory, which the elites always try to make them… it’s like power is never enough, wealth is never enough… but without the need, as Raymond Williams says, to negotiate with democratic forces, these societies wouldn’t last at all. They would collapse overnight. So paradoxically, that they last for as long as they do - the Roman Empire, The British Empire, the French Empire - is because we keep trying to re-establish moral communities. But eventually oligarchy, the tax it puts on the life system’s regenerative capacity, is such that the whole thing eventually falls apart.

To me gradual radicalism is realizing that if you’re looking at oligarchic societies today that do have aspects of the life system present, you’re not going to get people to tear the whole thing down. It’s just not rational to them, and I think that this is where sometimes the radical left can get very elitist and very disconnected from society. It’s not that everyone’s just stupid, it’s also that there are some really good reasons to look around you and be like, “Okay a lot of this sucks, but some parts of this are awesome and we want to keep them.” Like I talk about in the book, whether it is the Internet, whether it is the idea in Canada of universal healthcare, whether it’s the fact that there’s public services like schools, libraries, public parks, and social services.

The Gramscian approach is like you mentioned earlier with the idea of Double Movement. Those elements of the life system are your wedges, those are your ratchets. They are your contradictions, and you need to push and expand those spaces. I think that process can be very radical if it’s done with an ultimately radical goal in mind. We just don’t want to make things suck slightly less, we really want to fundamentally break this oligarchic stranglehold.

Aurora: Let me ask you to describe a ratchet because I think the reader has to think about how an evolutionary ratchet works.

Kevin MacKay: I took the idea of an evolutionary ratchet from Brian Ferguson, an anthropologist who has done seminal work on questions of power, oligarchy, and warfare. He was talking about it more in negative terms, in the sense that as oligarchic systems establish themselves, it gets harder and harder to come back from them. In particular, he showed how engaging in large-scale warfare creates profound changes in a society and leads to more despotic and authoritarian structures. But you can also have what I’ve called “ratchets in reverse.” There are also evolutionary ratchets that act in the direction of democracy. And you’re right about the analogy - a ratchet is the idea that you can easily turn it in one direction, but you can’t turn it in the other direction.

Aurora: Or the ratchet holds its place while you kind of recharge it to move it forward. That’s what came across for me. I’m thinking, “We’re constantly moving forward. We don’t slip away from that place of advance but we do take our focus and strategy back a bit to re-crank it, to move it forward again.”

Maybe I am too literal because I have those in my toolbox and I use them.

Kevin MacKay: Oh no, me too.

Aurora: But I was thinking, “Yeah, if you’re trying to think about a way to move forward” and you’re thinking of the really millions of alternatives that are out there. People are seeing the same things you’re describing and they’re creating a slow food movement or they’re creating a community energy project or they’re looking at, I don’t know, community generated elder care or affordable housing. How we bring all these gradual radical efforts together through as you called it a “movement of movements”, maybe we make a way forward. And I just want to close with you about how we might suture these multiple efforts together and have you thought about that?

Kevin MacKay: I have. For me Gramscian thought, and its further development by Ernesto Laclau and Chantalle Mouffe, has been useful. The Gramscian tradition is not only about describing how hegemony works, but also the process of counter-hegemony. Gramsci talks about the historic bloc - a number of groups that come together around common social goals, and that are historic in the sense that there’s a certain political moment they seize, a certain time where they’re able to see their collective interests converge.

Aurora: OK.

Kevin MacKay: And then that bloc might be powerful enough to overthrow the entire nexus of oligarchic control. I see radical transformation working in that way. Today there are a number of incredible local manifestations of the life system that are creative and that are productive and that have legs. And yet there’s also a disconnect between these different groups, and especially between projects led by different identity groups. So, you have amazing organizing being done by Black Lives Matter for instance, and by modern day feminists waging culture struggles, and you have a labour movement that’s still important and still fighting, even though it’s got real challenges. How do you bring these groups together?

To me it’s a very organic process of establishing a common vision and some sort of common practice for achieving it, a common social and political practice. You’ve got all these movements, but how do you create a vehicle that they can participate in which doesn’t ask them to stop being their own autonomous entities? Because I don’t think they can or should stop.

At this point in my life I’m a middle class white male, so I’m very privileged, but I’m interested in creating a vehicle through which women, visible minorities, LGBTQ folks and other underprivileged groups can realize a common degree of democratic participation, safety, security, and a sustainable future for their children. In the book, I talk about how, if you really looked at it, these groups have at least 80% of their interests in common. You’re never going to get 100% agreement, and I think it’s ridiculous to try because that 20% you’re not going to agree on is beautiful. That’s democracy. That’s the juice and the friction that’s going to keep your society moving forward and growing and developing. But that 80% is very real. We can ask “Do we have a fully representative democratic system where all those diverse groups can actually express their needs and desires? Do we have the rule of fair and just law?” Today we don’t have anything close to these things, and these are basic goals that we can all get behind and that, if we actually implemented them, would produce a society that is almost unrecognizable.

What I think is important is creating a vision of that 80%, a platform of that 80%, and a political vehicle to realize it. The devil’s in the details in terms of how you actually pull it off, but that’s where in the book I talk about four priorities of solidarity building, education, alternatives building and resistance. A conscious engagement with those four priorities is the way to build a movement of movements and to move forward.

Aurora: Is there anything else you want to say to close it?

Kevin MacKay: No, except that I appreciate the questions.

Aurora: And I really enjoyed the book. It’s got just the right balance of references for people who want to read more to learn how you arrive at certain conclusions, but it’s not a picket fence of footnotes and jargon.

Mostly I thought you gave us a new word. I think transformation eclipses transition. Everybody’s talking about transition. Yet, there’s a sense to the word transition that simply suggests we need changeover to a new technology - it’s renewable, it’s low carbon, it’s green and it aligns society around it - whereas radical transformation asks the tougher questions about democracy and human agency.

Kevin MacKay: I agree. If we see change as a passive process, or a technocratic process, or an exercise in reformism, then we’re not going to get there. Only breaking the oligarchic death grip on our culture’s creative potential will avert civilization’s crisis. This is a big task - in a sense no less than re-directing the course of human evolution. But despite this, it’s also possible. We have the capacity and the innate propensity to make this change, and the sooner we organize to do it, the better.

Aurora: Great to meet you again, and chat with you Kevin. Thanks.

Interview at Sky Dragon Cooperative, Hamilton, Ontario: Summer 2017.

Related Links

BT Books: Radical Transformation, Oligarchy, Collapse, and the Crisis of Civilization

Dr. Mike Gismondi is Professor Sociology and Global Studies, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences at Athabasca University.

Aurora Online

Citation Format

Gismondi, Mike. (2017) “Radical Transformation: An Interview with Kevin MacKay” Aurora Online