Aurora Online with Dr. Janice Morse

The Honorary Degree of Doctor of Science

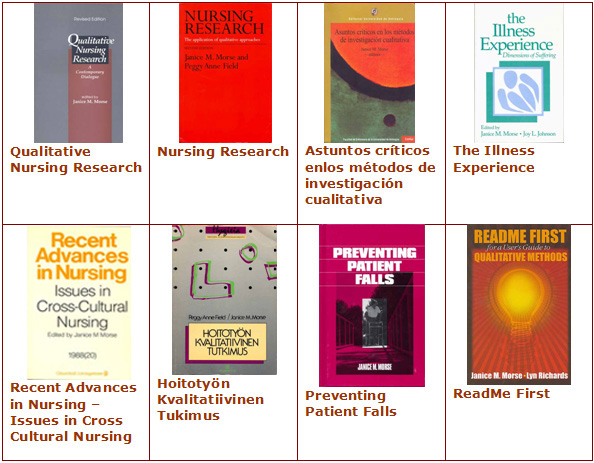

On Friday, June 13, 2008 an Honorary Doctor of Science will be conferred on Dr. Janice Morse, Professor and the Ida May “Dotty” Barnes, RN, and D. Keith Barnes, MD, Presidential Endowed Chair in the College of Nursing at the University of Utah. Dr. Morse has effectively reached an international audience of scholars in the fields of nursing and the health sciences. She has written extensively in the field of qualitative methodology, was instrumental in the conceptualization and building of the International Institute for Qualitative Methodology (based at the University of Alberta), is the founding editor of Qualitative Health Research, and has been called the “driving force” behind a new web-based journal, The International Journal of Qualitative Methods.

Comfort: Care + Cure

Dr. Janice Morse discusses

the significance of care in the work nurses do

Interview by Joan Bottorff, 1990

Listen to Aurora Audio Interview: Comfort: Care + Cure with Professor of Nursing - Janice Morse (Winter 1990)

Although we all recognize when we are being cared for or treated in a caring way, the term care is not easy to define. We feel that words comfort and care have slightly different meanings, yet their differences are not easy to pin down. To Dr. Janice Morse, a professor of nursing at the University of Alberta, these subtleties are important. She is conducting a major research project funded by the U.S. National Center for Nursing Research, NIH, to examine the concepts of comfort and caring in nursing. For her, an understanding of caring and comfort is important because care "is essential to keep families and societies and cultures and nations and human kind together," and because historically, care has been seen as the essence of nursing.

Since the early twentieth century, with the development of scientific medicine and a medical profession, the two functions of curing and caring were split. According to Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English in a book which summarizes the history of women healers, "Curing became the exclusive province of the doctor; caring was relegated to the nurse. All credit for the patient's recovery went to the doctor and his 'quick fix'. The nurse's activities, on the other hand, were barely distinguishable from those of a servant. She had no power, no magic, and no claim to the credit." Dr. Morse believes that nurses indeed deserve credit for the patient's recovery, and that one of their major contributions, that is, caring, is a necessary element in the curing process.

Aurora: We differentiate between care and cure. Are they mutually exclusive, as some people think they are?

Morse: No, they are not mutually exclusive, and I am very interested in diseases or pathologies for which there is no cure other than care. Chronic illnesses and psychiatric illnesses are examples of illnesses which can be medically controlled but not cured.

Aurora: So, is caring just a way out when we can't cure?

Morse: No, but we know that sometimes curing strategies without any care is ineffective. But putting a value on caring in the curing process is almost impossible. The interesting thing with medical research is that they try and remove all of the therapeutic effects of caring, which they call the placebo effect.

Aurora: I know you've done some work with native healers. Is this an example of combining the care and the cure?

Morse: Yes, it's wonderful! They combine all of the tricks in the hat to maximize themselves as therapists. The treatments, the cures, and the spiritual part of caring—they're all put in the hat at once. And if the purpose is to cure, that's how it should be. Why ignore something just because it's not considered scientific?

Aurora: What can western medicine learn from the native Indian healers?

Morse: The medicine man uses all the strategies of caring that nurses use along with the knowledge of a pharmacist and the practices of a physician. But in the end, he attributes cure or healing to the great spirit rather than taking credit himself, as our physicians do. I don't know if that means that medicine has something to learn from nursing, or that we should necessarily combine our roles. I don't want to suggest that we should stop our specialization, but I think that we could certainly stop our narrow thinking, that nursing is exclusively care and medicine is exclusively cure. It's a false dichotomy.

Aurora: Caring is supposedly a highly valued trait, yet there's no evidence of this value in monetary terms. Why are many caring professions not highly paid?

Morse: If you care, you're not supposed to work for dollars, and yet that's what nurses are hired to do. One of the problems traditionally with negotiating nurses' salary is society's attitude that "because you are an altruistic, caring person, you'll get your reward in heaven." The mentality of society generally is that you're supposed to care for people and not care about money. The other caring professions have the same problem. For example, teachers and clergy have had to struggle to be compensated adequately. It's not necessarily a problem inherent only in female professions, but largely it hits female professions. In some caring professions such as medicine and counselling psychology, caring has been subsumed for market place values. They certainly are not expected to provide services for free just because they care. The interesting thing is that medicine is struggling now to put some caring back into its philosophy.

Aurora: You've done some work on gift giving between patients and nurses as being reciprocity for care. How does that work?

Morse: One of the problems in our health care system today is that of an imbalance: nurses work for the hospital, and they give care to the patient. Unless patients have a chance to give back to the nurse, they are forever indebted to the nurse and therefore somewhat dependent. The dependency doesn't go away, which interferes with recovery and rehabilitation. In other parts of the world, in other cultures, there is the opportunity for the person being treated to give back to the traditional healer or midwife. We deny that in our culture. Hospitals get very uptight about such a gift-giving relationship. If patients do not have any opportunity to reciprocate, to give back to the care giver, then they tend to go off and repay their debt by doing something for other people. This is the basis of the twelfth step of the Alcoholics Anonymous recovery program. When patients give back to the nurses it is a symbol of their relationship. It is not something that's done because it's habit or because it's a cultural norm or because it's Christmas. The gift is very often reflective of that relationship so if the care has been very poor, then they give back by getting even or by sabotaging care or by not turning up for treatment. If the care has been excellent, then the gift is highly significant, both to the care giver and to the patient. It's a very important step in terminating the therapeutic relationship. Hospitals are trying to patrol or redirect these gifts to the hospital foundation. This is unfortunate because a gift to the hospital foundation is far too removed from the very intimate relationship between the care giver and the patient.

Aurora: Is it always expensive gifts or monetary gifts that are given?

Morse: No. In fact, the gift can be an intangible thing, a look or a thank-you or an apology. The gift can be worthless in a monetary sense, but at the same time have great significance for the nurse and the patient.

Aurora: How is the notion of comfort related to care and cure?

Morse: This is really a can of worms. Since the late 1970s, caring has been in vogue in nursing as the essence of nursing. Yet theorists writing on the subject have a great deal of trouble including all that nurses do under a caring framework. We have been trying to flip things around a bit and examine comfort as the purpose of nursing. Rather than saying that comfort is a part of caring, we're trying to say that caring is a part of comfort. Caring fits into what nurses do by providing the altruistic motivation for nurses to act and to make their actions humane, good, and gentle for the benefit of the patient. We're saying that comforting is caring plus what nurses actually do.

We're not throwing caring out; we're incorporating it in what we do.

Aurora: If caring is the motivator, then is it something that is constant in all situations?

Morse: No, caring is something that the individual must control in order to provide excellent care to a patient. For example, if a nurse cares a lot, it is not possible for her to inflict pain. But any nurse who works on a burn unit can tell you the strategies she uses to stop herself from caring so much that she feels the patient's pain. It's tricky. Surgeons do this, too; they shield themselves. They depersonalize their patients into a "case" so they can cut through the skin and do the surgery. Hospitals worry about nurses who become over involved because they tend to burn out or to meet the patient's need as a person rather than his or her therapeutic needs as a patient or the hospital's needs. A nurse who cares too much cannot care for all patients at that level. Caring too much for some patients will result in less care, or inferior care, for others.

Aurora: Are there ways to find out if caring really makes a difference to the patient?

Morse: Yes, but most studies have looked at the patient's psychological well-being or satisfaction. I think that whether or not someone receives good care should be evident in physiological terms, as well. In nursing, we have a false notion that the physician prescribes the care. The physician certainly prescribes the treatments, such as the pills or the antibiotics, but it's the nurse who is watching over the patient and who recognizes early signs of complications, who knows how to provide comfort measures, who knows what to offer the patient even before the patient complains of a dry mouth or a pain in the leg. The quality of assessment and the number of comfort measures provided is directly related to how much the nurse cares about the patient and cares about her job.

Aurora: Do you have any advice for the new nursing graduate about how much she should care or how to balance her caring?

Morse: No, I don't know how to make new graduates wise nurses. Research shows that nurses learn to become wise nurses through experience, by caring too much, by suffering because they care too much, and by withdrawing and bouncing around until they learn what level of involvement to reach with patients. I'm afraid I don't know how to tell them to be wise nurses right from the beginning.

Dr. Janice Morse, University of Utah

International Institute for Qualitative Methodology

The International Journal of Qualitative Methods

Cisneros-Puebla, César A. (2004, September). "Let's do More Theoretical Work ...": Janice Morse in Conversation With César A. Cisneros-Puebla [96 paragraphs]. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research [On-line Journal], 5(3), Art. 33.

Available at: http://www.qualitative-research.net/fqs-texte/3-04/04-3-33-e.htm.

Translated as "Hagamos más trabajo teórico". Janice Morse en conversación con César A. Cisneros-Puebla, FQS

http://www.qualitative-research.net/fqs-texte/3-04/04-3-33-s.htm

Joan Bottoroff is a former Athabasca University tutor and is currently the Dean of the Faculty of Health and Social Development at University of British Columbia - Okanagan.

Update: March 2018

Aurora Online

Citation Format

Bottorff, Joan (original interview published Winter 1990) Comfort: Care + Cure: An Interview with Dr. Janice Morse Aurora Online