Marx in Soho at the Athabasca Fringe 2005: An Interview with Actor and Sociologist Jerry Levy

Interview by

Mike Gismondi

Last summer I spent an enjoyable week sharing my home with US actor, sociologist, and small town character Jerry Levy. Jerry brought Howard Zinn's one-man play Marx in Soho - to the Athabasca Country Fringe, held every year on the third week of July in the Town of Athabasca. As a Fringe Festival supporter, I had offered to billet Jerry (sight unseen) but based on the following description - some '60s era sociologist from the States playing Karl Marx. Apparently the billeting captain figured we would get along (I am a sociologist, and known to own some books by Marx, and I was a teenager during the '60s, so she guessed right). It turns out we shared a love of the fringe theatre and a respect for Howard Zinns work. Both of us also teach at universities located in small rural towns and had been involved in local politics, which gave us much more to talk about. Over that week we palavered in the kitchen between technical setups and the three times Jerry offered the play. We talked about the draw of small-town life, acting, Zinn, the play, the war in Iraq and whether progressive Americans had lost hope; we also explored the boreal forest around Athabasca (the wild as Jerry called it) and ended up finding that we shared much in common.

Just so you know, Jerry drew a crowd to the Legion basement for each showing of Karl Marx in Soho. About 120 people young, old, right, left and just plain no where - came out to see Karl Marx over the weekend. Not bad for the

Athabasca Country Fringe The Little Fringe That Could.

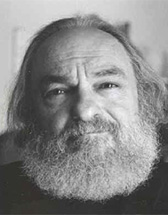

Local artist Joan Sherman sketched Jerry at work. Her work is interspersed throughout the interview.

Photo: Permission provided by Jerry Levy

Aurora: Jerry, we will get to Zinn and the play in a minute, but first can you tell us a little about yourself ? Where do you live, and how you come to be traveling the world with this particular play?

Jerry Levy: I live in Brattleboro, Vermont. I've lived there since 1975. I started coming up there in 1970 with the commune movement. I grew up in Chicago, lived there for 17 years and went to the University of Illinois. I lived in Washington DC for a year, and then I lived in New York for 13 years, where I got my PhD in Sociology and started teaching.

In 1970, southern Vermont was one of the rural meccas that people were flocking towards. Not just the communards, but there was a kind of anti-urban movement that was responding to the tumultuousness of the '60s and '70s. It happened after the '68 Democratic convention. The assassination of Martin Luther King, the assassination of Bobby Kennedy, and the debacle at the

Democratic convention. Protestors were beaten up in the streets, and inside the Democratic convention delegates were beaten up. The response to that was that you can't work within the system. The idea was to go to rural areas and start a new life and build a new society from the outside that would eventually take over the whole society. It didn't quite happen.

In 1970, southern Vermont was one of the rural meccas that people were flocking towards. Not just the communards, but there was a kind of anti-urban movement that was responding to the tumultuousness of the '60s and '70s. It happened after the '68 Democratic convention. The assassination of Martin Luther King, the assassination of Bobby Kennedy, and the debacle at the

Democratic convention. Protestors were beaten up in the streets, and inside the Democratic convention delegates were beaten up. The response to that was that you can't work within the system. The idea was to go to rural areas and start a new life and build a new society from the outside that would eventually take over the whole society. It didn't quite happen.

But anyway, I was a part of that. My marriage was breaking up. I was 30, I was footloose and fancy free. I was teaching at Adelphi University. When I arrived there, 15 percent of the students were hippies and zippies and yippies and politicos. I was part of the first generation of new left faculty. This guy comes into my class, his name is Stein. He says, come on Jerry, I'm taking you to my commune. So he brought me up there, sold me his teepee and his Volkswagen. I was living in New York at the time, and I lived on this zippy hippy commune and fell in love with Vermont and started coming up. Eventually I left my job at Adelphi and moved up in '75 to start a new life in Vermont.

Aurora: I understand that you went from the commune to the sociology department? What was that transition like?

Jerry Levy: When I got up there, a couple of friends of mine were teaching at Marlboro College. So they got me a course. Eventually that led to a fourth time position, then a half time position that had to be renewed every year. I finally got a full time tenured position after 11 years, in '86. But when I first started coming up there, I only wanted to

teach part time. I was going through some kind of 30 year old crisis, did I really want to be an academic? I'd been studying the violin seriously, and I was interested in the commune movement. So I moved up there and started doing

community theatre. Since I wasn't responsible for anybody but myself, I did - at the age of 30 - what the previous generation did when they were in their early 20s. I didn't go on the road. I came to Vermont and started living out this

rural life.

This was part of a major urban to rural migration, not just of youth, but of people of all ages. People were dropping out of corporations, and professionals were moving up because they wanted to have this more simple rural life. So I started doing a variety of things, and I stayed.

Aurora: You were telling me the other day that over the years the mix of people in the community changed quite a bit.

Jerry Levy: There was this major urban to rural migration. In some ways I would call it a new middle class migration, but there were working class people. There were propertied people moving up from Kentucky. There was a whole migration of people wanting to get away from urban areas which were filled with crime, trying to get away from the system that was promulgating the Vietnam War. It was a kind of the "cities on the hill" thing. You can start a new life. You can overthrow your previous life and replace it with some idealized life. So people came up. They wanted to farm, they wanted to engage in art outside of the system, they wanted alternative politics, they wanted good food, they wanted fresh air, they wanted a place to bring up their children. People wanted a place where they could experiment erotically, experiment with alternative education, different ways of bringing up your children. The Vermonters were very tolerant of this, because they had a history of utopian communities. The Oneida Community started there, where they had a system of

complex sexuality, a system of multiple marriage (See the Oneida Community-http://www.nyhistory.com/central/oneida.htm).

John Noyes had about 50 wives. He could control his ejaculations, that was his thing. Then there were all the men down low on the totem pole who couldn't. He was like this authoritarian figure who determined who was ready to have sex with whom. Eventually Noyes was thrown out of Vermont. But there was this tradition, so they welcomed the hippies.

A lot of educated middle class people moved to Vermont to live out their values and their ideology that they had picked up in the university, in the civil rights movement, in the women's movement, in the anti-Vietnam War movement, the environmental movement. Here was a place of a small enough scale where you could live that kind of life. That's what was driving them, and then there was also this ideology that we're going to withdraw. Hopelessly nave, but everybody bought it. We're going to withdraw from this society, and we're going to build our new society based on barter and ecological principles and growing your own food, building your own houses, creating your own culture and your art. We're going to withdraw from this, and eventually the old society will collapse because everyone will withdraw from it.

Well of course that didn't happen. What happened was the middle class people left the system, and the working class people were anxious to get into it and fill the spaces. Peter Berger once wrote an article called " The Blueing of America". As people withdraw from the system, that just creates opportunities for people who want to get in, in the corporate, bureaucratic, corrupt world. But that's what our legitimating ideology was at the time. I was part of that. My personal thing was that I had been teaching in New York and going on demonstrations and active in the anti-war movement. I was very frustrated, like everybody else, because the war seemed to go on and on and on. I was floundering in my life. I wanted to go to a place where I could really do something. And it worked for me. I found a place where, if you contributed anything to the culture, you were appreciated. What's the point of doing a play or giving a recital in New York? You're competing with the best people in the world. But in Brattleboro, anything you did was of some benefit to somebody. So I think that's what motivated me to go there, and I think that's what kept me there. I found a niche in life where I could teach, I could do some theatre, do some music, do some politics.

Well of course that didn't happen. What happened was the middle class people left the system, and the working class people were anxious to get into it and fill the spaces. Peter Berger once wrote an article called " The Blueing of America". As people withdraw from the system, that just creates opportunities for people who want to get in, in the corporate, bureaucratic, corrupt world. But that's what our legitimating ideology was at the time. I was part of that. My personal thing was that I had been teaching in New York and going on demonstrations and active in the anti-war movement. I was very frustrated, like everybody else, because the war seemed to go on and on and on. I was floundering in my life. I wanted to go to a place where I could really do something. And it worked for me. I found a place where, if you contributed anything to the culture, you were appreciated. What's the point of doing a play or giving a recital in New York? You're competing with the best people in the world. But in Brattleboro, anything you did was of some benefit to somebody. So I think that's what motivated me to go there, and I think that's what kept me there. I found a niche in life where I could teach, I could do some theatre, do some music, do some politics.

Aurora: Not just some politics. Tell me a bit about your public life in state politics.

Jerry Levy: I joined the Liberty Union Party, which was a kind of Socialist Anarchist party, like the Peace and Freedom Party and other small parties that were founded as a result of the Vietnam War. I joined the party. I'd been teaching US foreign policy, so instead of running for state legislature, (which I probably should have, though I didn't really even know enough to run for state legislature, I'd been there for three years), now I was going to run for the US Senate. So I did, and made quite a splash. New face on the block, got a lot of publicity, went around the state and got one percent of the vote. I did it again and again and again. One percent of the vote, seven or eight times. When there wasn't a US Senate race, I would run for Secretary of State. Some critics tried to increase the vote required for small parties to run candidates, so that instead of having to get five percent, they were going to make it 10 percent in a statewide race, to get rid of these liberal union people and the grassroots people (there were a bunch of little

political parties). So, then I ran for Secretary of State, with the agenda of getting 10 percent of the vote. I got six percent of the vote, didn't get close. Since then I've been active in local activist issues -- nuclear power plant

protests, stuff like that.

Aurora: You said to me this morning that you actually found that the Zinn play offered you a new chance to work

towards more effective changes.

Jerry Levy: You really never know the results of your actions. As a teacher, as an activist and environmentalist, you never know what you contribute to social change. You hope. You act, and you hope. But I've found that as a result of doing this play -- I've performed it 27 times now on the east coast, west coast, and now Canada that people are very interested in Howard Zinn's "Marx in Soho". For you Canadians who don't know him,

Howard Zinn is this famous American activist and scholar, who in 1980 wrote A People's History of the United States. It's a best selling  book, it's sold probably millions of copies. Everywhere you go, (and I would call them lovers of Howard Zinn) his followers come out. If he's giving a lecture they'll come out - 500, or a 1,000 people. If they're showing his documentary, they come. They just love him and love everything he touches. He's like a grandfather figure in American politics. If we had a social movement of any consequence, he would be one of the leaders, and he is one of the leaders, and would be an elder statesman. If he was a little younger he'd be, well...he's kind of a Martin Luther King type. He's that resonant on so many levels.

book, it's sold probably millions of copies. Everywhere you go, (and I would call them lovers of Howard Zinn) his followers come out. If he's giving a lecture they'll come out - 500, or a 1,000 people. If they're showing his documentary, they come. They just love him and love everything he touches. He's like a grandfather figure in American politics. If we had a social movement of any consequence, he would be one of the leaders, and he is one of the leaders, and would be an elder statesman. If he was a little younger he'd be, well...he's kind of a Martin Luther King type. He's that resonant on so many levels.

Anyway, I read his play "Marx in Soho", which is a play about Karl Marx coming back after being dead for 100 years. He's pissed off because it's the fall of the Soviet Union and they've declared that not only is he dead, but his ideas are dead forever. Communism is dead, the nails are in the coffin. He comes back and he's living in this other worldly place for controversial political, religious, and artistic leaders. He says, I want to go back, I'm so misrepresented. Well the committee in the afterworld allows him to go back. Marx grew up in Soho, in London, England but through a bureaucratic mistake, he ends up in Soho, New York. There's this audience, and he's telling them about his life and his ideas and his relationship with his family, and his views, everything he's seen in the last 100 years. He saying, my ideas are still relevant, capitalism is doomed. But, in this play, its a more mellow, easygoing, sensitive, likeable Marx.

Zinn portrays him this way, so I'm trying to represent Zinn's representation of Marx, which I live.

I think Marx is an important historical figure. I think he's worth bringing up and looking at every once in a while during these terrible times in the United States, in the belly of the beast, the evil empire destroying the rest of the world. We activists in the United States are very frightened, very frustrated, and very angry, and feeling very impotent at the same time, with the Bush administration. So Zinns play is complex, well thought-out and realistic; a feel-good play for activists, for people who want to know a little bit about Marx, for people who maybe just want a kind of secular quasi-religious ceremony they can gather around. And for people who've never been exposed to Marx, I think its a very good introduction.

Aurora: You told me that you've really found an audience, one that you had not expected and that on this tour you've been invited by community groups and communities across the west

Jerry Levy: I have my man, my outreach coordinator, who's emailing. I'm computer illiterate. But he's emailing me and finding venues for me. I've just been to Portland and now the Athabasca Fringe Festival, a wonderful festival that you all should go to. And wonderful for the performers, because they're treated so well. Then I'm going other places on the West Coast, peace groups, socialist groups, a Marxist school in Sacramento. It'll be interesting to find out what they're all about, they got me down for four nights. I'm on sabbatical, so I have nine months to tour this play to death. I

hope to go Europe with it too. I view it on a number of levels: to perform the play, to meet people, to have them tell me about their lives and their situations. I'm interested in political economy, I'm interested in how globalization is affecting a particular town, a particular rural area, a particular region. I'm interested in how different classes and status groups are making out economically and socially and culturally, in the niche that they're trying to find in this global political age.

So now, I'm in a farming community in the wilds of Alberta. It's wild. My friend Mike is a sociologist, and he's showing me around. In a sense I'm doing fieldwork too, trying to find out more. But like all good fieldworkers, I'm willing to talk about myself and what I know.

Aurora: We had a realization the other day that we both are professors teaching in very small communities. Athabasca is 2,500, it's a bit bigger where you are. Could we talk some more about being an academic in a rural small town?

Jerry Levy: In Brattleboro where I teach at Marlboro College, the college is one of dozens of alternative institutions that were started after World War II, but particularly in the '60s and '70s and '80s that accompanied this rural migration. There are solar institutes, there's a school for international training, there's Landmark College, which is a school for dyslexics, there's everyone's institute fantasy. There's writers' workshops,  there's music festivals. Brattleboro and the surrounding area is invested with alternative institutions that have been started by migrants from urban areas, who basically have created in institutional form the fantasies of what they wanted to do. Just like when they build their dream house in the outlying town, they either buy up an old house and fix it up, or they build a new house which is their environmental dream. Brattleboro culture is many-faceted. It's new age, it's leftist, it's progressive, it's artistic, it's feminist. It's all of the ideologies and directions which the '60s and '70s went in American society. The broad scale revolt against western civilization in the United States has congealed in Brattleboro. So there's radical bookstores, there's coffee shops, there's theatres, there's a dance center. Everything that an urban person would want. So it's very attractive to artists, professors, intellectuals. People are flocking there. The difficulty for them is making a living because for every job for a professor, there are 20 professors or retiring professors that would love to work here. When we do a search, say at Marlboro College for a new professor, 300 people apply. I know, because I've been on some of these search committees. Then we pared it down to 20 people, and then three or four finalists. Each of them

comes for a day, we run them through the mill, and we make a decision. From our point of view, we should be getting the crme de la crme. We get very good people. But think of all those people who don't get jobs. Some people move there anyway and they can't get jobs, so they commute to other places or find other things to do. This is true in psychotherapy, it's true in alternative medicine, regular medicine: there are three times the number of people trying to sell their services in a limited market. So it's like everybody's trying to start their little business, their little sheep farm, their cheese farm, their organic farm, their this, their that, everything under the sun. There's almost too much culture, too much production with not enough consumption.

there's music festivals. Brattleboro and the surrounding area is invested with alternative institutions that have been started by migrants from urban areas, who basically have created in institutional form the fantasies of what they wanted to do. Just like when they build their dream house in the outlying town, they either buy up an old house and fix it up, or they build a new house which is their environmental dream. Brattleboro culture is many-faceted. It's new age, it's leftist, it's progressive, it's artistic, it's feminist. It's all of the ideologies and directions which the '60s and '70s went in American society. The broad scale revolt against western civilization in the United States has congealed in Brattleboro. So there's radical bookstores, there's coffee shops, there's theatres, there's a dance center. Everything that an urban person would want. So it's very attractive to artists, professors, intellectuals. People are flocking there. The difficulty for them is making a living because for every job for a professor, there are 20 professors or retiring professors that would love to work here. When we do a search, say at Marlboro College for a new professor, 300 people apply. I know, because I've been on some of these search committees. Then we pared it down to 20 people, and then three or four finalists. Each of them

comes for a day, we run them through the mill, and we make a decision. From our point of view, we should be getting the crme de la crme. We get very good people. But think of all those people who don't get jobs. Some people move there anyway and they can't get jobs, so they commute to other places or find other things to do. This is true in psychotherapy, it's true in alternative medicine, regular medicine: there are three times the number of people trying to sell their services in a limited market. So it's like everybody's trying to start their little business, their little sheep farm, their cheese farm, their organic farm, their this, their that, everything under the sun. There's almost too much culture, too much production with not enough consumption.

With regard to the college, people are willing to come there at a very low salary. Our incoming salary is $36,000, maybe a little more. The spread between the incoming salary and the highest salary is maybe $12,000 or $15,000. So the senior faculty get a job here, you can't get a job anywhere else. To get a job somewhere else you have to be a distinguished professor who's published an important book. Marlboro rewards teaching, not publishing. You don't have to publish anything to get tenure at Marlboro College. So from the point of view of getting a job somewhere else, you're kind of stuck there. And they know they've got you forever, so they're not going to raise your salary. Also, it's a small college that's struggling to survive. So they raise the base pay, but they don't raise the upper pay. The senior professors, the tenured

ones, (and there's no rank you're either junior or senior faculty, and when you're senior faculty you're tenured), you're kind of stuck there. But the younger people will come because it's a good place to raise families. It's very attractive, because there's really interesting schools and all sorts of interesting stuff going on.

Aurora: You don't sound stuck there, Jerry.

Jerry Levy: No, I'm not complaining. I've had a wonderful run.

Aurora: Can I ask you about your music? You've been shy about it, but you're a musician.

Jerry Levy: I was for many years a very serious amateur violinist. I probably would say that music is my first love. Growing up, I decided not to be a musician, because I wasn't good enough. In those days, Jewish boy growing up in a secular Jewish family, the way you make your way in the world is you are the best at what you do. I knew I wasn't going to be the best, so I went another direction. But this need to play music didn't go away.  So I started again studying the violin when I was 30, and got better and better to the point where I was a pretty good amateur and maybe a semi-professional with a special talent. So I started playing chamber music up there again. I gave some recitals and performed chamber music. Being a musician is like being an athlete. You have to be able to sustain it. For my 60th birthday, this wonderful pianist, Louis Poitier, who's an assistant to Rudolph Serkin, asked me if I had stopped playing because I had some physical problem. He said, when are you going to start playing again? Well, I said, I'm going to play this year, and I'm going to perform all of the Mozart violin piano sonatas. The next day he called and said he would perform them with me. So I practiced and practiced and practiced. I performed many of them. And we started giving them. The first recital, I had to stop. I didn't have the staying power. So that was a big crisis. I said, I'm going to stop until my body loosens up. Then I just stopped. I threw it all into theatre. I'm going to take up the violin again, but not working towards performance. I've been doing theatre. When I came up to Brattleboro in the '70s I started doing community theatre. I've been acting for 35 years, and I've had really good roles. Now I'm focusing on theatre, but I love music. Any time I can find a live classical concert, I go.

So I started again studying the violin when I was 30, and got better and better to the point where I was a pretty good amateur and maybe a semi-professional with a special talent. So I started playing chamber music up there again. I gave some recitals and performed chamber music. Being a musician is like being an athlete. You have to be able to sustain it. For my 60th birthday, this wonderful pianist, Louis Poitier, who's an assistant to Rudolph Serkin, asked me if I had stopped playing because I had some physical problem. He said, when are you going to start playing again? Well, I said, I'm going to play this year, and I'm going to perform all of the Mozart violin piano sonatas. The next day he called and said he would perform them with me. So I practiced and practiced and practiced. I performed many of them. And we started giving them. The first recital, I had to stop. I didn't have the staying power. So that was a big crisis. I said, I'm going to stop until my body loosens up. Then I just stopped. I threw it all into theatre. I'm going to take up the violin again, but not working towards performance. I've been doing theatre. When I came up to Brattleboro in the '70s I started doing community theatre. I've been acting for 35 years, and I've had really good roles. Now I'm focusing on theatre, but I love music. Any time I can find a live classical concert, I go.

Aurora: So how did you find this play by Zinn?

Jerry Levy: These friends of mine, Stan and Barbara Charkey, he's a music professor at Marlboro College, and we're very close friends. We eat dinner together once or twice a week. They had read this play and they said, Oh Jerry, you've got to read this play. This is perfect for you. An actor is always looking for a good part. I read the play and that was it. It seemed to express everything I felt about Marx and the current context of society.

Zinn and Eric Fromm are very generous when they deal with Marx, especially Fromm. Eric Fromm can say nothing bad against Marx. Zinn's portrait is a very generous one, but also I wouldn't call it a whitewash. He does portray some of his less attractive qualities, I hope. And I felt that I have the physical type, I've

taught Marx for most of my adult life, I thought the play was well written, and for some reason I knew I could do it. So, I wrote Zinn a long letter, raving about the play, how I thought it was so important at this time. I wanted to

bring this play to a larger audience. I started telling him about myself. He wrote back a short note saying, thank you for your kind words. Perhaps you could send me a video before I allow you to do it locally. I could understand that.

He's not out to make money with this play. He wants his ideas to be represented responsibly. Not just anyone can memorize forty-nine pages of text, and pull it off. I respect that very much. So I did the video, and he liked it.

I've been doing it for about a year now. He and his wife, Roz came to see it. There's a wonderful documentary about his life, based on a book he wrote, You Can't be Neutral on a Moving Train. If you're interested in Howard Zinn, you should read it. This documentary is like that. So I saw her on the documentary. When they came to Brandeis University to see the play, I went up to her and said, I met you on the documentary. They both liked the play very much. It was a thrill to do it for them. It gave me a special energy. I'd like to think it was a good performance. They liked it. The fact that they like it is very important. Whatever my limitations as an actor, I feel their support and acceptance, which is very important to me.

I've been doing it for about a year now. He and his wife, Roz came to see it. There's a wonderful documentary about his life, based on a book he wrote, You Can't be Neutral on a Moving Train. If you're interested in Howard Zinn, you should read it. This documentary is like that. So I saw her on the documentary. When they came to Brandeis University to see the play, I went up to her and said, I met you on the documentary. They both liked the play very much. It was a thrill to do it for them. It gave me a special energy. I'd like to think it was a good performance. They liked it. The fact that they like it is very important. Whatever my limitations as an actor, I feel their support and acceptance, which is very important to me.

Aurora: You mentioned that you had taken the play outside the States once before coming to Canada, and that was to the Dominican Republic.

Jerry Levy: I did. I have a former student, a woman who studied with me and then studied with Arthur Vidich at the New School for Social Research. She went down to Santo Domingo and started a small foundation which provides services to the rural poor outside Santo Domingo. Families who have lost their land and are either working in the new textile sweatshops, are unemployed, or are prostitutes or are going to Santo Domingo trying to get something. The poorest communities. She goes to the schools there, she brings artists there, she provides crafts, art, helps with the soup kitchens so they can get a good meal. She's doing whatever a social worker can do in a situation like that. She invited me down, and she has contacts with the activists, the youth, the artists, intellectuals. She invited me down to give a couple of performances of "Marx in Soho", and maybe give some talks on US foreign policy, which I love to do. In all my years as a candidate for the United States Senate, and teaching US foreign policy, nobody ever invited me, even in Vermont where I'm known, to give a talk on US foreign policy, which is one of my specialties. So I was able to give a couple of talks on US foreign policy at local universities in Santo Domingo to large audiences. They are very interested

in what somebody from the belly of the beast has to say. So I gave performances, I gave some lectures, I gave some workshops. It was wonderful, about the same as my experience here in Athabasca. Just wonderful.

Mike Gismondi is Professor Sociology and Global Studies, Faculty of Humanities and Social Science at Athabasca University.

Related Links

Jerry Levy: http://www.levyarts.com/index.html

Update: March 2018

Aurora Online

Citation Format

Mike Gismondi (2006) Marx in Soho at the Athabasca Fringe 2005: An Interview with Jerry Levy Aurora Online

In 1970, southern Vermont was one of the rural meccas that people were flocking towards. Not just the communards, but there was a kind of anti-urban movement that was responding to the tumultuousness of the '60s and '70s. It happened after the '68 Democratic convention. The assassination of Martin Luther King, the assassination of Bobby Kennedy, and the debacle at the

Democratic convention. Protestors were beaten up in the streets, and inside the Democratic convention delegates were beaten up. The response to that was that you can't work within the system. The idea was to go to rural areas and start a new life and build a new society from the outside that would eventually take over the whole society. It didn't quite happen.

In 1970, southern Vermont was one of the rural meccas that people were flocking towards. Not just the communards, but there was a kind of anti-urban movement that was responding to the tumultuousness of the '60s and '70s. It happened after the '68 Democratic convention. The assassination of Martin Luther King, the assassination of Bobby Kennedy, and the debacle at the

Democratic convention. Protestors were beaten up in the streets, and inside the Democratic convention delegates were beaten up. The response to that was that you can't work within the system. The idea was to go to rural areas and start a new life and build a new society from the outside that would eventually take over the whole society. It didn't quite happen.

Well of course that didn't happen. What happened was the middle class people left the system, and the working class people were anxious to get into it and fill the spaces. Peter Berger once wrote an article called "

Well of course that didn't happen. What happened was the middle class people left the system, and the working class people were anxious to get into it and fill the spaces. Peter Berger once wrote an article called " book, it's sold probably millions of copies. Everywhere you go, (and I would call them lovers of Howard Zinn) his followers come out. If he's giving a lecture they'll come out - 500, or a 1,000 people. If they're showing his documentary, they come. They just love him and love everything he touches. He's like a grandfather figure in American politics. If we had a social movement of any consequence, he would be one of the leaders, and he is one of the leaders, and would be an elder statesman. If he was a little younger he'd be, well...he's kind of a Martin Luther King type. He's that resonant on so many levels.

book, it's sold probably millions of copies. Everywhere you go, (and I would call them lovers of Howard Zinn) his followers come out. If he's giving a lecture they'll come out - 500, or a 1,000 people. If they're showing his documentary, they come. They just love him and love everything he touches. He's like a grandfather figure in American politics. If we had a social movement of any consequence, he would be one of the leaders, and he is one of the leaders, and would be an elder statesman. If he was a little younger he'd be, well...he's kind of a Martin Luther King type. He's that resonant on so many levels. there's music festivals. Brattleboro and the surrounding area is invested with alternative institutions that have been started by migrants from urban areas, who basically have created in institutional form the fantasies of what they wanted to do. Just like when they build their dream house in the outlying town, they either buy up an old house and fix it up, or they build a new house which is their environmental dream.

there's music festivals. Brattleboro and the surrounding area is invested with alternative institutions that have been started by migrants from urban areas, who basically have created in institutional form the fantasies of what they wanted to do. Just like when they build their dream house in the outlying town, they either buy up an old house and fix it up, or they build a new house which is their environmental dream.  So I started again studying the violin when I was 30, and got better and better to the point where I was a pretty good amateur and maybe a semi-professional with a special talent. So I started playing chamber music up there again. I gave some recitals and performed chamber music. Being a musician is like being an athlete. You have to be able to sustain it. For my 60th birthday, this wonderful pianist, Louis Poitier, who's an assistant to Rudolph Serkin, asked me if I had stopped playing because I had some physical problem. He said, when are you going to start playing again? Well, I said, I'm going to play this year, and I'm going to perform all of the Mozart violin piano sonatas. The next day he called and said he would perform them with me. So I practiced and practiced and practiced. I performed many of them. And we started giving them. The first recital, I had to stop. I didn't have the staying power. So that was a big crisis. I said, I'm going to stop until my body loosens up. Then I just stopped. I threw it all into theatre. I'm going to take up the violin again, but not working towards performance. I've been doing theatre. When I came up to Brattleboro in the '70s I started doing community theatre. I've been acting for 35 years, and I've had really good roles. Now I'm focusing on theatre, but I love music. Any time I can find a live classical concert, I go.

So I started again studying the violin when I was 30, and got better and better to the point where I was a pretty good amateur and maybe a semi-professional with a special talent. So I started playing chamber music up there again. I gave some recitals and performed chamber music. Being a musician is like being an athlete. You have to be able to sustain it. For my 60th birthday, this wonderful pianist, Louis Poitier, who's an assistant to Rudolph Serkin, asked me if I had stopped playing because I had some physical problem. He said, when are you going to start playing again? Well, I said, I'm going to play this year, and I'm going to perform all of the Mozart violin piano sonatas. The next day he called and said he would perform them with me. So I practiced and practiced and practiced. I performed many of them. And we started giving them. The first recital, I had to stop. I didn't have the staying power. So that was a big crisis. I said, I'm going to stop until my body loosens up. Then I just stopped. I threw it all into theatre. I'm going to take up the violin again, but not working towards performance. I've been doing theatre. When I came up to Brattleboro in the '70s I started doing community theatre. I've been acting for 35 years, and I've had really good roles. Now I'm focusing on theatre, but I love music. Any time I can find a live classical concert, I go. I've been doing it for about a year now. He and his wife, Roz came to see it. There's a wonderful documentary about his life, based on a book he wrote,

I've been doing it for about a year now. He and his wife, Roz came to see it. There's a wonderful documentary about his life, based on a book he wrote,