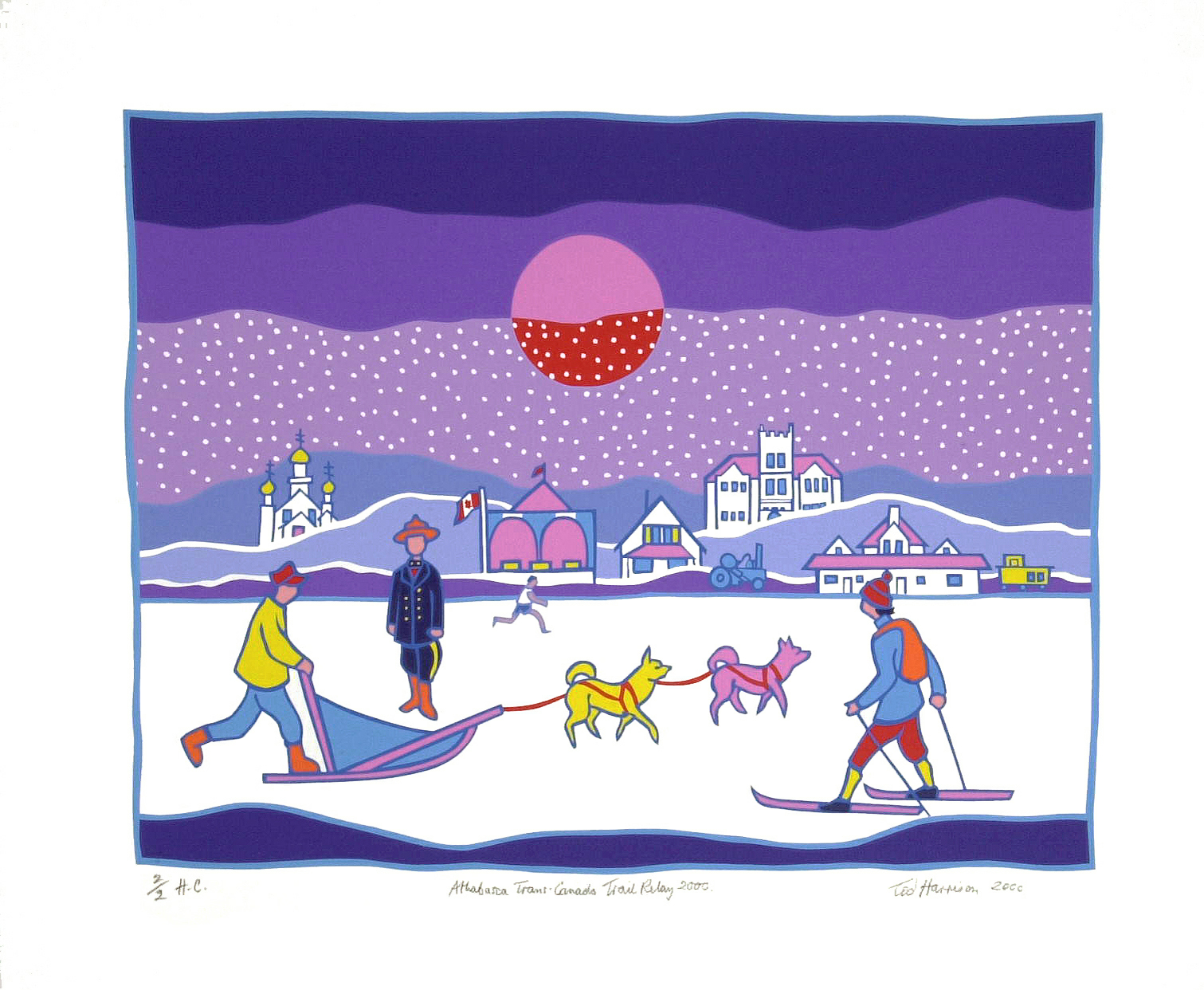

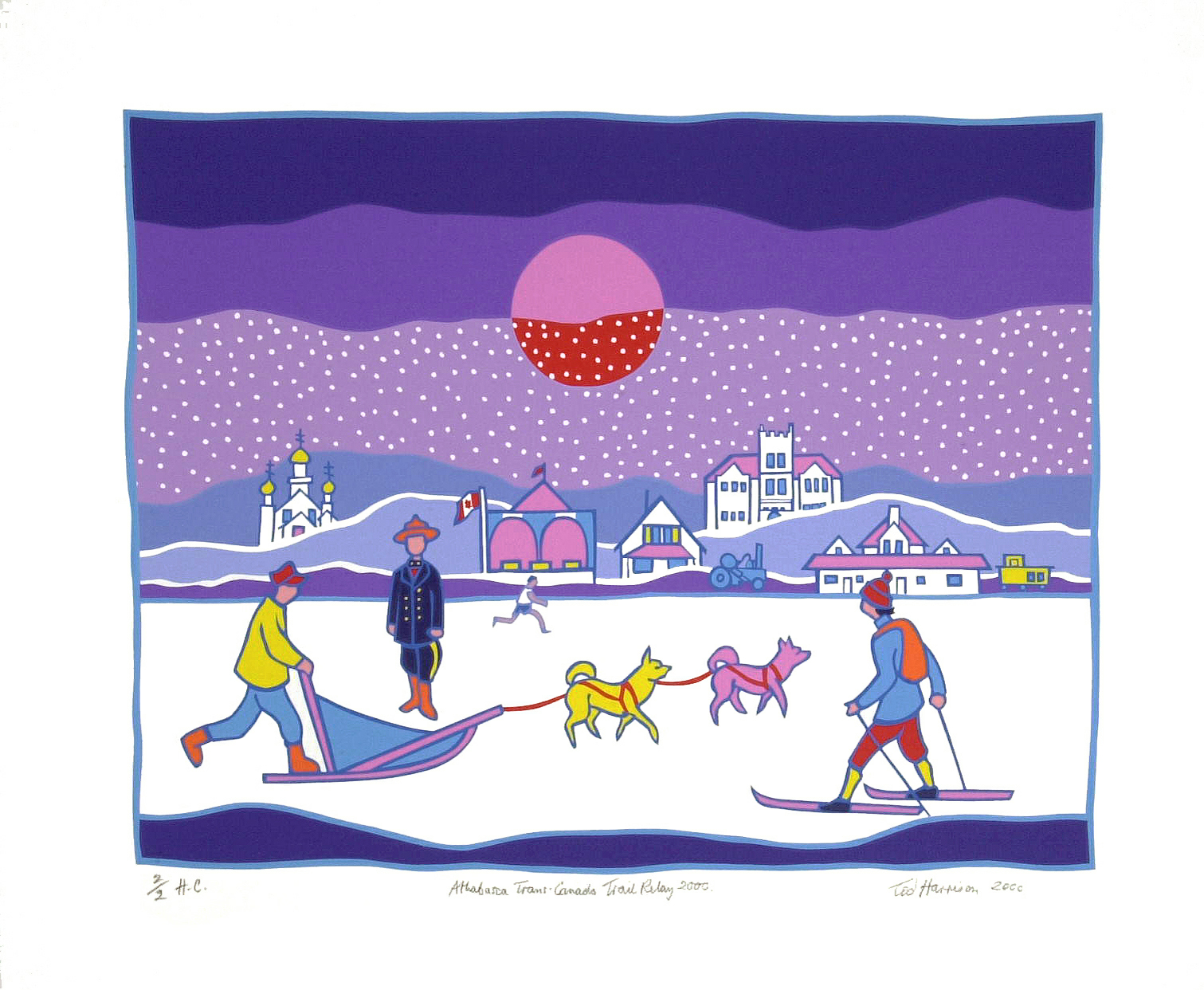

Click on image for larger view.

Click on image for larger view.

A Pint Of Mild And Bitter

Interview by Ross Paul

Like his well—known poet predecessor, Robert Service, Yukon artist Ted Harrison left his native northern England and, after extensive travel, discovered the Canadian North. His bright and vibrant paintings vividly portray both the rugged landscape and the special spirituality of the Yukon. Writer, teacher, and illustrator as well, Ted Harrison has a unique perspective on art, on the North, and on the special attributes and challenges that define Canada. He was interviewed by teleconference from his home in Porter Creek, a suburb of Whitehorse.

Aurora: On a very cold and clear evening last February, I was doing the very Canadian thing of driving back to Edmonton from Athabasca after playing hockey. It was about one o'clock in the morning, and I noticed that the Northern Lights displayed the most incredible moving colours I had ever seen—bright greens and pinks. It suddenly came to me that “Ted Harrison was right. He didn't just make up all those bright colours.” I read that one of the tributes that meant the most to you happened when you shared a similar experience with an Inuit friend who turned to you and said, “Look! A Ted Harrison sky!”

Harrison: That's correct.

Aurora: This emphasizes how much an artist is a product of his or her own environment. 1 understand that you began to use bright colours only after you started living in the Yukon. Would you now paint the same way back in your native County Durham in England?

Harrison: No, I don't think I would. I have two paintings in my basement from those early days. There are elements of my present style in them, but on the whole, they seem very grey and drab. I wouldn't be able to paint Durham my old way because my whole philosophy has changed since those days.

Aurora: People come from Saudi Arabia to see your work, and you have had a showing in New York. Do people who lack the experience of the North react differently to your paintings?

Harrison: Well, I had some interesting feedback in New York. I was going to the gallery early one Sunday morning when a young lady stopped me and asked if I was Ted Harrison. She said, “I've just been looking at your work in the gallery, and I find it intensely spiritual.” And then she added, “This is what New York needs.” She disappeared, and I never saw her again. A number of people have told me that they found a spiritual quality in my work.

Aurora: Do you remember when you first thought of yourself as an artist?

Harrison: When I was a student, I wanted to be what I pictured a real artist to be, but I didn't think it really could happen. Finally, when I found that I could leave teaching and live off my art, I recognized that I had made it as an artist in the material sense. But I really became an artist before that— when I changed my style in the Yukon. It came right out of the blue. I actually created something new, which I hadn't known existed within me. Previously, I had tried to paint the landscape in an academic style, which was quite boring although I could do it easily if you practice and practice, like a piano player, you get this facility. I could paint landscapes that looked like landscapes. Then I changed my style to one, which looked, as if I'd never had an art lesson in my life, although I'd studied the subject for five years as a student. I feel that I am an artist now; I felt it the first time I changed my style. I found later, in analysing this change, that I'd thrown all my academic knowledge into the wastebasket. Of course, I then had to bring back certain elements of it, so my style today is a combination of that early style as the foundation with new elements superimposed on it. I never forced these, but have always waited for them to come. Even though it may look like I'm doing the same thing each time, each painting has something new in it.

Aurora: So it's not as if you're just churning out what a certain population wants to see.

Harrison: It's like driving down an English country lane—there are many bends, and you never know what is ‘round the corner. It's this not knowing what is ‘round the corner that is so special. Once I had a visitor's book at a local show in which someone wrote “same old stuff.” I thought that interesting because the person had recognized my style. He couldn't say “same old à la Picasso, you see. It was my same old stuff, so I didn't take it negatively at all.

Aurora: You're so distinct in your style. Are there young Harrison clones coming along who are trying to emulate your style?

Harrison: Yes, apparently there are. The best cloning story is about a young Chinese boy in Vancouver whose parents took him back to their native village in China some years ago. He took along reproductions of my work, which he had in his bedroom and gave them to the local villagers and showed them to the village art society. I don't know where that village was, but I heard recently about Harrison—like works coming out of China and being sold in Hong Kong. I thought this was fantastic. I'd love to go to that village.

Aurora: I read an article which drew parallels between your work and cloissoné, the enamel and copper work done in Cloisson, France. Was this a formal influence on your work, or is it a result of a similar spirituality emanating from two different environments?

Harrison: Actually, I went to see an exhibition in Toronto of the Cloissonist School of Painting. I found that a Cloissonist is defined as a person who paints a strong line around an object. I guess Van Gogh was one. Critics and journalists are always wanting to label my work and to put it in a niche where it can stand in the art world. So I've told them that I am a Canadian neo— Cloissonist, which sounds really nice but is still quite vague. So that's what I am, a Canadian neo—Cloissonist!

Aurora: One of the hallmarks of your style is that both the mood and subject of your paintings are peaceful and tranquil. Yet, I understand your war experiences weren't all happy ones, and life in the Yukon often has a very dark side. Is there a dark side that's come out or might still come out one day in your painting? For example, you are preparing a new children's book on the Alaska Pan Handle and the Exxon oil spill. Will there be a more political side to this book? Would you paint an oil spill, for instance?

Harrison: No, I wouldn't paint an oil spill, but I have had rather hidden elements of violence in some of my painting. For instance, I once went to Watson Lake where there was a good fight in the bar. Somebody was smashed over the head with a guitar. I later did a painting of a guy lying on the floor in front of all those Watson Lake sign posts.

Elements of loneliness also come into my painting to reflect alienation, of the native people in particular. They're in lonely little villages, or they're lonely with great skies above them, or you'll find women with children but no man in the picture. The mother is solely looking after them. It's not so much deliberate and conscious, but more a reflection of what I see around me. These things creep into my paintings. Interestingly enough, I've got a twin sister who lives in England, and I find occasionally I put twins in my paintings—they just pop in accidentally somehow.

Aurora: So you paint what you feel and see rather than deliberately sit down to portray a particular political issue.

Harrison: You see, people know political issues, and many schools of painting do that extremely well. Blood and gore go all over the canvas. People know the world's in a mess without having it hung at home. People have individual strife and troubles in their lives so some peace and contentment is required.

I've been reinforced in this philosophy by two psychiatrists. One was an Albertan, and the other was a Japanese psychiatrist in Colby. They both had reproductions of mine hanging in their waiting rooms and told me that these had a very calming effect on their patients. I think the elements and the colour in the paintings have a soothing effect.

A lady from Saskatchewan once wrote me that if she carried her two year old past a painting of mine hanging in the house, the child would scream to be taken back to look at it and would instantly calm down. Maybe I've invented a new type of soother, as well as a work of art.

Aurora: That would be a good marketing device. Someone reading this who is not familiar with your work might picture pastels and peaceful, soft colours. Yet we're talking about strong contrasts, heavy lines, and often hot colours in a cold environment.

Harrison: I think my paintings show that there are areas of tranquility in the world, and I look upon where I live as part of that. The Yukon is quite a magical spot. It can have a calming effect. Heaven knows we have enough social and political problems here to fill a book, but the overall effect of the landscape is quite calming. Today, for instance, while we're talking, the temperature is minus forty degrees, and just before you came on the phone we had a half—hour electricity cut, and the temperature in the house began to drop. These are things you learn to treat with a certain calmness. If the power had not come back on, I'd have had to leave the phone and get a bonfire going!

Aurora: You retired as a teacher when you thought you could make a living as an artist, but you've also continued writing, especially for children. Do you still think of yourself as a teacher?

Harrison: I'm often invited to visit classrooms. It's rather interesting that people ask my advice on education now that I've quit teaching. They never asked my advice while I was a teacher. I like the classroom. I think it's the most important battleground in the whole country, and I see a lot of the ills of society coming from bad parenting and bad teaching. But I don't have much faith in a lot of the mechanical aids to teaching. I think we need more humanism in education.

When giving talks I try to show that art, music, poetry, and literature are as important as the sciences. The problem is that we tend to put them all in compartments. Somehow, we must get back to a more humanistic and integrated approach and treat science, art, music, and poetry as extremely important and not deny children access to all these wonderful things.

Aurora: I'm interested in your use of acrylics. Did this just happen, or did you experiment with a number of media until you found the right one?

Harrison: When I was a student in the early part of the war, we didn't have acrylics, and canvas was hard to come by, so we had to use oils and paint on stretched sugar sacks. Well, oils are allright, but they're messy and smelly and take a long time to dry. When acrylics came along, I wasn't too successful at first, but I experimented and read about them and now find them a very elastic medium. They're clean, and they only use water for mixing so you spill water rather than turpentine all over the floor, and you get neither the smell nor the ill—health now associated with breathing turps all day. Besides, I can get the effect I want with them, and the simple nature of my style suits acrylics.

Aurora: Do you work quickly?

Harrison: Yes, I do. Once I get an idea, I usually have a white canvas in front of me. I then sit and look at it a while until pictures form and I can actually see the whole picture finished. Then, I just go to it, and it sort of grows as I'm working. I couldn't plan it out in the beginning. I once had a commission given by the local government here for a big painting. They wanted a kind of cartoon, a prepainted image to see what it would be like, and I told them I couldn't do it that way, preplanning the way I used to work as a student. They accepted that and got what they wanted. For me, it's stilted to work it all out first. I know that other artists have different methods, but everyone's different, and that's how it should be.

Aurora: I don't get the impression that you would come back and fiddle with a painting then, but more that you would paint it straight off.

Harrison: That's right.

Aurora: How long does it usually take you to do one of your paintings?

Harrison: Well, it depends; some take a week and some take a day. About two days on the average, I'd say.

Aurora: Are you systematic in your hours, or do you paint only when you feel like it?

Harrison: Well, I may sit down in the morning or sometimes I go downtown and then start about one o'clock and work through till ten or eleven at night and just go after it in one nice big block.

Aurora: You complete something like 75 paintings a year?

Harrison: Yes, something like that.

Aurora: Are there some that you just won't sell, or do you wish you had not sold some of them?

Harrison: There are some favourites I don't have anymore, but they're in good hands. I always think, well, when it leaves me, if it goes to an exhibition or somebody pays the price for one, they're not going to hang it up in the outhouse. They're going to look after it.

Aurora: Do you still feel an ownership for every painting? If you see something you painted ten years ago, what do you think about it?

Harrison: Well, I feel I've met an old friend. I once saw a painting in a house I visited. I went up to it and said, “Hello, what are you doing here?” and chatted with it. The owner of the painting said, “Oh, you remember painting that one?” I said, “I sure do.” In fact, I remember incidents that happened while I was painting a particular picture.

Aurora: I had an interesting experience quite a long time ago when I worked at a camp north of Montreal. One night we were back at the camp and there was nothing particularly planned. Somebody had some oil paints so we all got together and painted our own versions of a reproduction of a Group of Seven painting someone had.

Harrison: There weren't seven of you, were there?

Aurora: No, there were ten, unfortunately. We never became too well known but even though none of us had painted much before, three out of the ten had real talent. These were adults in their thirties and forties who had never realized what talents they had. Was this an unusual experience?

Harrison: No, I think it's quite common actually. I have known people whose whole life was changed by finding they had a flair for art. I once ran a night school in New Zealand for adult students, one of whom was a very troubled lady. She was being helped by a psychiatrist to deal with great fits of depression and lots of conflict with her family. Because she was sick of doing all the chores at home, she decided to come to my class. At first, she just giggled or complained in a loud voice that she was no good, and I got pressure from the rest of the class to kick her out. But eventually she became quiet and worked away at it. After a year, she showed her paintings to the psychiatrist, and he told her she didn't have to see him any more. Then she had her work shown in a gallery and told her family they could make their own dinners and do the washing up because she was going out sketching. She was really liberated through art. I often look back on her case, and I think it's remarkable how her art gave her this wonderful freedom. Her faith and self—esteem rose a hundred per cent!

Aurora: And that's a very important theme for you, isn't it, as exemplified in some of your children's books like The Blue Raven with its strong emphasis on independence and believing in yourself.

Harrison: That's right. I had a student who hated school and everything that comes with it. In junior high, he came into my art class and was no good at painting and drawing. Absolutely hopeless. He deserved a zero, but then he found that he could handle clay, and suddenly this kid did amazing things like ancient Greek heads in clay. A sociologist from the University of Alberta came up on a visit and couldn't believe that the work was done by a high school kid and not an adult. That kid eventually dropped out of school, but he had shown sheer genius with clay, and I don't suppose he ever did anything quite like it again.

Aurora: One of my favourite books is the beautiful version of Robert Service's The Cremation of Sam McGee which you illustrated so perfectly. I am struck by the parallels between you and Service. Wasn't he also from your neck of the woods?

Harrison: He was born in Lancashire and at a very early age moved up to Scotland. Our lives are similar in some ways. We both came to the Yukon almost by accident and found it liberating in many ways. He became a poet, and I became an artist, reflecting what I call the magic of this place. I often wonder if I'd gone to live in another part of Canada whether I would have painted the same—I don't think so.

Aurora: Well, I can't think of anybody who has done so much to increase the awareness of the North and its beauty, not just the beauty of the landscape but the spiritual beauty so evident in your paintings—the sense of freedom tinged with tragedy and loneliness.

Harrison: Thank you for your compliments and interest in the work. I was thinking we should have chatted in an English pub somewhere.

Aurora: As someone who has lived in England off and on over the years, I would very much enjoy a chat with you over a pint or two.

Harrison: Now there's a great art form—a pint of mild and bitter!

Click on image for larger view.

Click on image for larger view.

A Northern Alphabet. Montreal: Tundra Books, 1982.

The Last Horizon. Toronto: Merritt Publishers, 1980.

Children of the Yukon. Montreal: Tundra Books, 1977.

Article originally published Spring 1990

Ted Harrison now resides in Victoria, British Columbia, where he still actively paints. Awards and honours include the Order of Canada in 1987, as well as being the first Canadian to have book illustrations selected for the International Childrens' Book Exhibition in Bologna, Italy.

He has received honorary doctorates at Athabasca University in Alberta in 1991, and in Fine Arts from the University of Victoria in 1998.

Updated March 2002

Aurora Online

Citation Format

Paul, Ross (1990). A Pint Of Mild And Bitter: A Conversation With Ted Harrison. Aurora Online: