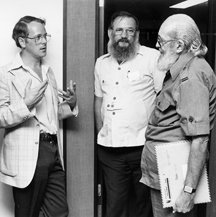

Paolo

Freire (r) at

Athabasca University, Alberta

Twenty Years Later: Similar Problems, Different Solutions

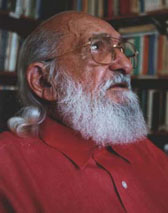

Brazilian educator and philosopher Paulo Freire has been defined by the famous Swiss educator Pierre Furter as “a myth in his own lifetime.” He has become an outstanding figure in the academic world for his unique combination of theory with practical experience in the field of adult education. Freire became famous in the early sixties for his powerful method for literacy training, but his writings went beyond mere techniques for literacy training and became a landmark for critical pedagogy all over the world.

His personal involvement with important literacy campaigns and innovative experiences in adult education in the Third World (Brazil prior to 1964, Chile, Nicaragua, Guinea-Bissau, Sao Tome, Cabo Verde, Principe, and Tanzania) have brought unique insights into very complex matters. His writing has impacted women's and worker's education in Europe, even as a source of contradiction, and his new analyses on the role of liberating pedagogy in the industrially advanced societies (see his books with Ira Shor and Donaldo Macedo) are currently important subject for debate and pedagogical thinking. It will not be an exaggeration to say that as John Dewey was the dominant figure in pedagogy in the first half of the century, Paulo Freire has been the catalyst, if not the prime “animateur,” for pedagogical innovation and change in the second half of this century.

Freire has received several doctorates, awards, and prizes for his work, including the UNESCO Peace Prize in 1987. In 1985 he and his late wife, Elza, received the Prize for Christian Educators in the United States. The importance of his work is expressed in the fact that his most important books (Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Education for Critical Consciousness, Pedagogy in Process: Letters from Guinea Bissau) have been translated into many languages including German, Italian, Spanish, Korean, Japanese, and French. Some of them, notably Pedagogy of the Oppressed, have more than 35 reprints in Spanish, 19 in Portuguese, and 12 in English.

Freire's recent book with Macedo (1987) calls for a view of literacy as cultural politics. That is, literacy training should not only provide reading, writing, and numeracy, but it should be considered”...a set of practices that functions to either empower or disempower people.” Literacy (for Freire and Macedo) is analyzed according to whether it serves to reproduce existing social formations or serves as a set of cultural practices that promote democratic and emancipatory change.” (Freire and Macedo, 1987:viii.) Literacy as cultural politics is also related in Freire's work to emancipatory theory and critical theory of society. Hence, emancipatory literacy “becomes a vehicle by which the oppressed are equipped with the necessary tools to reappropriate their history, culture, and language practices” (Freire and Macedo, 1987:159).

In short, Paulo Freire is currently one of the most vibrant educators and political philosophers of education. The long-term impact of his pedagogical thinking will evolve well into the next century.

This interview was conducted by Carlos Alberto Torres in 1990 and translated by Paul Belanger. Paulo Freire died in 1997.

Aurora : Twenty years ago you wrote your influential bookPedagogy of the Oppressed, based on your educational experiences in Brazil and Chile. This book has had a profound impact on contemporary pedagogy. Why did you decide to write this educational book? What is the history behindPedagogy of the Oppressed, seen in perspective, 20 years later?

Freire: I think the first thing I ought to say is that I write about what I do. In other words, my books are as if they were theoretical reports of my practice. In the case of Pedagogy of the Oppressed, I started to write it exactly at the beginning of 1968, after the second or third year of my exile. What happened? When I left Brazil and went into exile, I passed my time firstly learning to live with a borrowed reality, which was the reality of exile. Secondly, I struggled with my original context which was the context of Brazil and which I saw myself forced to abandon. From afar, I began to take stock of Brazil and therefore to take stock of and to analyze my earlier practice, discovering in it things the new context of borrowed reality was making me discover. So there was a moment, naturally, when I began to arrive at a more radical understanding of my own work. And supported together with the experience of Chile, made in quasi-comparison with the earlier experience of Brazil, I felt the need of putting to paper another moment of my pedagogic and political experience. Pedagogy of the Oppressed appeared as a practical, theoretical necessity in my professional career.

Aurora: How did that title occur to you?

Freire: That is also interesting. My books earn a title even before they are written. Pedagogy of the Oppressed, which I think is one of my best titles, came to mind during the process of my experience in Chile, and it repeated many of my earlier experiences of Brazil.

Secondly, the title came as a need to underscore the existence of another pedagogy, which is the pedagogy of the oppressor. I intended, with the title Pedagogy of the Oppressed, to distinguish this type of pedagogy from the existence of another pedagogy which, even though it existed, had concealed itself under other titles, under other names.

I was preoccupied also with calling to attention the role of the subject, and not that of pure actor, 1for the working classes in the process of their own liberation. Hence the title of “Pedagogy of Oppressed People” which, in a general way, is also expressed in the singular. Fundamentally, my preoccupation was with a pedagogy of oppressed people, in the plural. But it ended up in the singular as Pedagogy of the Oppressed.2

Aurora : I would now like to take you from Latin America to the United Stated and Canada. You have recently published two influential books in the United States in collaboration with Ira Shore and Donaldo Macedo. And you know the United States and Canada very well from your constant lecturing and visiting of both countries. How do you think the political philosophy underlying Pedagogy of the Oppressed could be applied in teachers training in these two industrialized societies?

Paolo

Freire (r) at

Athabasca University, Alberta

Freire: I am going to try and say it in simple terms and begin with an understanding of what teaching is, and therefore education and training of both educators and students. For me, the process of formation of educators necessarily implies the act of teaching, which should be developed by the teacher, and the act of learning, which should be developed by an apprentice.

It is necessary to clarify what teaching is and what learning is. For me, teaching is the form or the act of knowing, which the professor or educator exercises; it takes as its witness the student. This act of knowing is given to the student as a testimony, so that the student will not merely act as a learner. In other words, teaching is the form that the teacher or educator possesses to bear witness to the student on what knowing is, so that the student will also know instead of simply learn. For that reason, the process of learning implies the learning of the object that ought to be learned. This preoccupation has nothing to do exclusively with the teaching of literacy skills. This preoccupation establishes the act of teaching and the act of learning as fundamental moments in the general process of knowledge, a process of which the educator on the one hand and the educatee on the other are a part. And this process implies a subjective stance. It is impossible that a person, not being the subject of his own curiosity, can truly grasp the object of his knowledge.

Now, when you ask me, “Paulo, how do you see your proposal at the First World level and not only at the level of literacy training?” I say to you that it is a question of the theory of knowledge that I established in pedagogical form in the Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Therefore, it also has to do with a democratic option. If an educator in Canada or the United States, who is neither authoritarian nor traditional, understands that his job of teaching demands the critical task of knowing on the part of his educatees, then there is no way not to apply this also in Canada. Canadians and Americans, since they are part of the First World, have not ceased to involve themselves daily in the process of knowledge.

Aurora: Is it possible to develop the pedagogy of the oppressed with a rational pedagogy and a pedagogy at the same time radical in the political context of a hegemonic power like the United States?

Freire: That is a very important question. Education practice is part of the superstructure of any society. In the end, for that very reason, educational practice, in spite of its fantastic importance in the socio-historical processes of the transformation of societies, nevertheless, is not in itself the key to transformation, even if it is fundamental. Dialectically, education is not the key to transformation, but transformation is in itself educational.

The question that you raise, Carlos, also seems to me to be founded necessarily on the other problem, which is the problem of political option and decision. In the first place, with respect to a democratic pedagogy, there is no reason why it cannot be applied simply because we are dealing the First World. Secondly, what is needed is to deepen the democratic angle of this pedagogy, which I am defending. And this deepening and widening of the horizon of democratic practice will necessarily involve the political and ideological options of the social groups that carry out this pedagogy. So, obviously, a power elite will not enjoy putting in place and practicing a pedagogical form or expression that adds to the social contradictions which reveal the power of the elite classes. It would be naive to think that a power elite would reveal itself through a pedagogical process that, in the end, would work against the elite itself.

Aurora: You proposed the term “conscientization” 20 years ago. And now you are proposing conscientization and the pedagogy of the oppressed once again in Brazil. What is the difference between now and 20 years ago?

Freire: Some of the fundamental problems that my generation had to confront in the past 25 years continue to be the same. I will tell you two or three of those problems that my generation confronted and that my grandchildren's generation now confront.

Brazilian illiteracy, on account of which I ended up expelled from my country, continues to be a growing problem even in the Brazil of today. The number of school-age children who do not reach the schools is another absurdity that continues to accompany the political and social life of Brazil. Today we have eight million Brazilian children prevented from being in school. The number of children who are pushed out of school, known in the official pedagogy as “scholastic evasion” or academic drop-out, continues to be a problem for the educators of today just as it was a problem for the educators of 30 or 40 years ago.

In my generation, we had the issue of domination by foreign capital, which we spoke of as the consignment of profits to foreign lands. Today, we still have the power of the multinationals. The lack of decorum, the lack of shame in Brazilian political and public life, which was a problem of my generation, is an immense problem today. Economic inflation ends up by spoiling our ethics and so lays waste to the entire depth of society. These problems, which were problems of my era, continue to be problems now. However, the answer is not the same. It cannot be the same. The literacy training I practiced 25 years ago, I am not going to repeat today.

We are now launching in Sao Paulo something called Mova Sao Paulo, a movement of literacy and post-literacy training. We have to confront in Sao Paulo today 1.5 million illiterate people. And we have to make a contribution or give testimony to the fact that with public power, if one has political will, something can be done.

Today, I am Secretary of Education for the city of Sao Paulo, with much more clarity, with much more political and pedagogical understanding, I hope, than when I was 30 or 35 years old. I see things more clearly now, and I feel more radical, but never sectarian, in the face of the reality of my country. I have a more lucid vision of what we must do to change schooling from the public school we have now, into a school that is happy, into a school that is rigorous, into a school that works democratically. A school in which teachers and students know together and in which the teacher teaches, but while teaching, does not domesticate the student, who, upon learning, will end up also by teaching the teacher.

If you were to ask me, “Are you attempting to put into practice the concepts that you described in your book?” of course I am, but in a manner in keeping with the times. It is one thing to write down concepts in books, but it is another to embody those concepts in praxis. Those things are showing themselves to be very challenging, but they continue to give me a sense of joy and satisfaction. It is not perchance that I find myself even younger now, because I am struggling to give the minimum contribution in the radical line of the pedagogy of liberation.

Aurora: There is a kind of wind of optimism coming from the south that fills me. I certainly find you younger everyday, since everyday you are more optimistic, and it is good to know that you are making headway in putting into practice your pedagogy with so much enthusiasm. What is the relationship between the political compromise of a socialist intellectual member of a party, and the possibilities and limits of education in the context of Brazil today, the possibilities and limits that promoted a transformational education in the context of modern Brazil? What is your sense of the situation at this time?

Freire: I am going to tell you something that you are going to understand, you who are a man who thinks dialectically and not only talks of dialectics. You must know intellectuals who talk about dialectics very well, but who do not think dialectically.

Today I live the enormous emotion of perceiving, everyday that passes, that the strength of education resides exactly in its limitation. The efficiency of education resides in the impossibility of doing everything. The limits of education could bring a naive man or woman to desperation. A dialectical man discovers in the limits of education the raison d'être for his efficiency. It is in this way that I feel that I am today an efficient secretary of education, because I am limited.

The following books can be ordered from http://www.amazon.com

Pedagogy of the Heart.1997.

Letters to Cristina: Reflections on My Life and Work. 1996.

Pedagogy of Hope. Reliving Pedagogy of the Oppressed.1995.

Pedagogy of the City1993.

Literacy: Reading the Word and the World.1987.

A Pedagogy for Liberation: Dialogues on Transforming Education. 1987.

The Politics of Education:Culture, Power and Liberation. 1985.

Pedagogy of the Oppressed.1970.

1 Interviewer's note: The role of the subject refers to the workers taking

their destiny into their own hands, while the notion of "pure actor" merely

refers to someone who might be acting a role in a play, but who has no control

over his own discourse or actions.

2 Translator's Note: The English

translation loses some of the Spanish meaning here. Freire juxtaposes the

expression los oprimidos with el oprimido, which English renders as "the

oppressed" in both instances

© Copyright 1999 AURORA

Citation Format

Torres, Carlos. (1990). Aurora interview with Paulo FREIRE: Aurora Online: