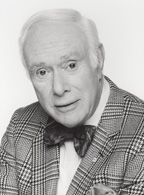

Pierre Berton is one of Canada's most prolific and popular authors and an accomplished story teller. The author of 46 books, Berton's literary career has been diverse. From books on popular culture to critiques of mainline religion, to picture and coffee table books to anthologies, to books for children to readable, historical works for youth, Berton has challenged and entertained us.

For this massive contribution to Canadian literature and history, he has been awarded more than a dozen honourary degrees. He was awarded a Doctorate of Athabasca University in 1982 “in recognition of his eminence as an historian, writer, and commentator, and of his concern for, and dedication to, Canada.” He has received over 30 literary awards such as the Governor-General's Award for Creative Non-Fiction (three times), the Stephen Leacock Medal of Humour, and the Gabrielle Leger National Heritage Award.

Berton is well known as a journalist and a media personality. He wrote columns for and was editor of Maclean's magazine, appeared on CBC's public affairs program Close- Up and was a permanent fixture on Front Page Challenge for 39 years. He was a columnist and editor for the Toronto Star and was a writer and host of a series of CBC programs, including The Pierre Berton Show, My Country, The Great Debate,and Heritage Theatre.

Of his nearly 50 works, a large number may be classified as history, including nearly 25 for the children and youth audience. All his works are eminently readable and hold the attention of the professional historian and the lay reader alike. It is not often that we encounter individuals whose research is so thorough and whose interpretations challenging but who can also capture the notice of professional historians and retain a following among individuals who simply want to know more of Canada's heritage.

The attraction of Berton's chronicle of Canada's past and present is noticeable, in part, by sales: Klondike sold more than 150,000 copies, an extraordinary number for any Canadian book, let alone a book of non-fiction

Berton continues to employ research associates and explore new fields of scholarship. His next volume, Marching as to War is expected in 2001. Although best known for his articulation of Canadian history, Berton has reflected on his life and times, and on Canada and Canadians, their values and idiosyncrasies, including Pierre Berton's Canada, Farewell to the Twentieth Century:A Compendium of the Absurd (1996 and 1998) and Welcome to the 21st Century: More Absurdities from Our Time (1999).

While many professional historians may lament his, at times, uncritical eye or his belief in the Canadian dream, each volume adds to our understanding of ourselves and our nation. Each volume attests to the skill of Mr. Berton and his research colleagues in seeking out the esoteric and the key resources to prepare his books.

Of his historical works, nearly 20 titles centre on the North, perhaps because Berton was born and grew up in the Yukon and retains strong attachments to these territories or because the North holds a fascination for Canadians and for many Europeans.

The following interview focuses on his book The Arctic Grail The Quest for the Northwest Passage and the North Pole, 1818-1909. In this book, Berton presents a narrative account of the heroic efforts of British, American, and Scandinavian explorers as they sought out the Northwest Passage through Canada's northern archipelago and the North Pole.

But this history is more than simply a narrative of heroic venture. Berton demonstrates the romantic impetus, poor planning, and administrative bungling that was involved in many of these expeditions, especially those sponsored by the British Admiralty, and the heroism of the officers and men. Moreover, his history of Arctic exploration is a study of the personal and professional motivations that underlay many the expeditions of Robert Peary, the great American seeker after the North Pole. Peary is exposed as much as a fortune seeker as a geographic explorer.

When The Arctic Grail was written, few other than professional historians or archeaologists had begun to explore the role of aboriginal peoples in Arctic exploration, including the search for Sir John Franklin. Pierre Berton deserves credit for bringing to the attention of the non-academic public the role of the aboriginal peoples in Arctic exploration. He rightly asserts that Arctic exploration, whether it be Peary's search after the North Pole or Amundsen's successful navigation of the Northwest Passage, would not have been successful without the participation of the native peoples of Greenland and Canada's North and their intimate cultural and scientific knowledge of the vast territories. Only gradually is our ignorance of the knowledge of these aboriginal peoples of their environment and the way in which they have interacted with that often “hostile” region being removed. Michael Owen

This interview was originally published in the spring 1990 of Athabasca University's Aurora magazine. The interview was conducted by Dr. Michael Owen, who is now Director, Research Services, Ryerson Polytechnic University.

Aurora: Were nineteenth-century quests for the Northwest Passage and the North Pole the equivalent of the search for the Holy Grail, and were the knights of the Arctic Grail similar to those who sought the Holy Grail?

Berton: Well, there were some parallels certainly. First, there was no damn use going there at all. It was simply a romantic adventure with the end point being meaningless. The Northwest Passage had no commercial value and neither did the North Pole. It was just a reference point on the map.

These quests were really romantic, quasi-religious endeavours. This perspective is enhanced by fact that the British gave “crusader” names to their sledges, names such as “Indominable.” Before setting out, the British explorers lined up their sledges, pennants streaming, and then headed off across the barrens, the men hauling the sledges. If they had used dogs to pull sledges, they could have been much more efficient. The British, however, weren't interested in efficiency. They were really interested in testing themselves against nature. Doing it the hard way seems to have been a British, Victorian Age idea. I think it was damn foolish myself!

Aurora: Why were the expedition leaders so willing to risk their own lives and the lives of others in this search for the elusive Grail? Were they seeking after honours, power, or position?

Berton:Not entirely. The men went because it was part of their job and because they received double pay. In the years following the Napoleonic War [1815-1818], the British Navy had too many officers and not enough for them to do. Most of them were on half pay and had no hope of promotion unless they became involved in some dare-devil enterprise. So they were eager to go to the Arctic, not because of the Arctic itself, but because that was the only way they could get a full-paying job and the only way they could hope for promotion. Some of them were romantics, too.

Aurora: From the bureaucrats' perspective, was Arctic exploration one means to maintain the British Navy's budget and manpower?

Berton: The Navy had to have something for their ships and their men to do. When the war with France ended, the British Royal Navy decided to map the world with a series of hydrographic maps of the oceans, the channels, the bays, and the inlets of the Arctic, and this itself was quite valuable. It was not just the Arctic; they also mapped the South Seas.

Aurora: Why were explorers and naval bureaucrats so unaware of the unpredictability of the Arctic environment, and why did they disregard the experience of previous and contemporary seekers of the Passage?

Berton: Well, Royal Navy bureaucrats and officers were very arrogant. They thought they knew more about the seas than anybody else. But the whalers knew more about the Arctic than the naval men, and if the latter had listened to William Scorsby, a whaler with much experience in the Arctic, they might have saved themselves a lot of time and trouble. They wouldn't do that. They looked down upon the whalers, with that snobbishness which is so much a part of the English upper class. That proved to be their undoing.

Another major problem was that the British explorers attempted to recreate their environment in the Arctic instead of coming to terms with the environment which they encountered, whether in the Arctic or in the South Seas. Colonialists dressed in British wool, whether it was 100 degrees in the shade or 40 below. Wool certainly was not suitable in India where cotton was more appropriate. In the North wool wasn't as suitable as furs, which was what the Inuit were wearing. But the British were blind to this. They thought they had the best of all possible worlds. This was Victorian snobbery and Victorian arrogance.

Aurora: Why were the British so obsessed by the search for the Northwest Passage?

Berton: Originally, the Northwest Passage was seen as a viable economic canal through the continent of North America which would allow them to get the spices and silks from the Orient, products that every body craved. Later, it became obvious that that canal didn't exist. Getting a ship through the Northwest Passage today is almost impossible, as even the biggest oil tankers have discovered. But old ideas die hard, and the Northwest Passage became like the peak of Everest, something that you simply conquered because it was there.

Aurora: Were the British obsessed with gaining the Northwest Passage because they feared that the upstart Americans or the Russians might beat them to it?

Berton:Oh yes! You have to remember that Russia has always been a great competitor with the western world. In the nineteenth century, Russia was seen just as much an economic rival as it was later seen a political rival. Russian territory ended at the Alaska-Yukon boundary. The Russians had done a lot of exploring in the North. They were in direct competition with the Hudson's Bay Company, which didn't want them anywhere near their territories.

I think, however, the Russians were more interested in the commercial value of seals and furs off the coast of Alaska and in trading with the Inuit than in exploration. Yet part of it was simply like the Olympic Games, where you want your boys to be the first.

Aurora: Why, in an age of science, did the Royal Geographical Society and the British public ignore the more spectacular aspects of the voyages of the North, for example, the discovery and the rediscovery of the petrified polar forests?

Berton: Well, it was the age of science, but it was also the age of exploration. British and American adventurers sought to solve geographical and scientific puzzles all around the world. One of the great puzzles was the source of the Nile. Another great puzzle was whether the Congo was the same as the Nile. Did these two great rivers join up? In finding out the answers to these puzzles, a great deal of knowledge was contributed to the world, but the ancillary discoveries were so many and so great that they failed, I think, to make the public presses.

Aurora: Of the Arctic explorers, the Americans were motivated by the least honourable passions, fame and fortune; the British appeared to have been the most stubborn and romantic; and the Scandinavians were the most objective seekers after scientific truth. How do you account for these “national” differences?

Berton: Scandinavians were northerners. They lived on the perimeter of the Arctic. They knew what cold was like. They knew what the conditions were like. They had experimented with skis. They were more phlegmatic, perhaps less romantically minded. I think all explorers are a very peculiar breed. They are an obsessed group, whether they are Americans or Scandinavians or British. Some thought God had ordered them to do it, as the American explorer Charles Hall did. Some wanted to be famous, as Robert Peary did. Others wanted a promotion. And some, such as Raold Amundsen, just wanted the credit of finding something. They were all terribly obsessed and willing to go to great lengths to beggar themselves financially; to leave home, wives, and families; to endure the greatest hardships–if they could only find the Grail. In that sense, they were like the knights of old.

Aurora: Of the Arctic explorers, Sir John Franklin, Robert Peary, and Raold Amundsen are the most famous. Franklin's various expeditions, as well as his career, encapsulate both the romance and the pathos of Arctic exploration. What is your impression of this man?

Berton: Well, almost everybody who knew him liked him, and the fact that two of the most stubborn and dominating women in all of England married him tells you a little bit about that. He was also easy going. He was brave, but he was not terribly ambitious.

His second wife, Lady Jane, was far more ambitious for him than he was. It was she who goaded him to get out of the back-water posting in the Mediterranean, and encouraged him to become governor of Van Dieman's Land [Tasmania], of all places, where he was not very effective because he was too naive and too trustworthy to realize the machinations of the civil servants around him. They finally forced his exit, and it was that loss of honor that caused him to go back to the Arctic to regain what he thought he'd lost–his honor.

The other thing about Franklin was he was very religious, as so many were in those days, but Franklin a little more than others. He wouldn't read anything but the Bible on Sunday, and this was the cause of some problems with his first wife, who died when he was in the Arctic. He was genial, I think quite sensitive, not a very good explorer, probably not a very good leader of men as subsequent events proved, not a good administrator, but a nice guy.

Aurora: What was the role of the British press in keeping the searches going for the lost Franklin expedition?

Berton:Well, the attention of the British press to the lost Franklin expedition did force the Royal Navy to continue the search. Yet another part of it was simply that conventional thinking conspired against common sense. The press, the Admiralty, and the Arctic alumni thought that Franklin had gone north when in fact he hadn't. They thought he couldn't have gone south into the Prince of Wales Strait because for years it had been jammed with ice. It never got through to them for a long time that the Arctic climate is unpredictable. The Arctic climate is so different from year to year, that a channel can be open one year and closed the next. They thought of the Arctic as a static environment where nothing changed, nothing moved. The Arctic is a very frenetic environment. Thus Franklin, who did go northward into Lancaster Strait, was blocked by ice, turned south, and was able instead to get right through where nobody believed he could. That's why they didn't look to the south to King William Island where he was.

Aurora: The last Franklin expedition in 1845 was supposedly the best equipped and planned expedition. What went wrong?

Berton: One thing that went wrong was they ate too much salt meat. Even the birds they shot, they salted down. This killed the vitamins and left them susceptible to scurvy. Then there was the business about the lead in the tin cans that were used to preserve supplies brought from England. Recent discoveries suggest that the lead in the tin cans probably contributed to deaths, but what I would like to know is how much lead there was in the body of the average English man in the mid-nineteenth century. Did the men who went on Arctic voyages already suffer from lead poisoning before they left?

Also Franklin had the wrong ships. These weren't coastal freighters that could manoeuvre those narrow channels. They were built for the oceans, built for fighting. In the end we don't know what really caused Franklin's death or the death of 20 or 30 men before the remaining crew abandoned ship. My theory is that probably scurvy and starvation contributed to their deaths, because a lot of the meat had gone rotten. If you take only salt meat and no fresh vegetables or fresh food, by the third year you'll come down with scurvy. This was true for every expedition that went to the North.

These explorers were not hunters. As Englishmen, they were used to shooting grouse on the moors. They didn't know anything about shooting big game and didn't have the weapons for it. Not only that, but they made absolutely no contact in the three-year period with Eskimo hunters who could have brought them meat. Nor were they able to make use of the caches of food that were at Prince Regent's Inlet, left behind by John Ross on his expeditions. They were sailors and didn't leave the ships very much. The interesting thing was that they didn't do much exploration inland.

Aurora: Franklin was so close to his goal of discovering the Northwest Passage when he died in 1847. Could his crew have been rescued? Could they have completed this voyage of discovery?

Berton: Oh, yes, they could have gone on. Lieutenant Francis Crozier, second-in- command, was an experienced Arctic hand. But by the time they set out from the ship it was too late. In fact they had two years to do some exploring, two years to find that out, two years to meet the Inuit who could have helped them, and they apparently didn't take advantage of these opportunities. The Great Fish River was probably not a very good place to go because I don't think they would have been rescued if they had gone to the mouth of the Great Fish River. In fact some of them almost got there, weren't rescued, and died. Rescue was unlikely and getting down that river is, as George Back who was on the first Franklin overland expedition in the early 1820s, found out is very, very difficult. A more promising direction would have been to go up to the Prince Regent Inlet to the cache of goods that John Ross had left in the1830s, but that was a long arduous trip too.

Aurora: Why is Franklin's stature as an Arctic explorer so great?

Berton:He would have been forgotten much earlier if Lady Jane hadn't kept at it. She was an activist and a voluminous writer of letters to famous people. Long after the Navy wanted the search stopped, she kept it going because public opinion was behind her. In the end, the Navy did stop because the Crimean War came along. That's when she hired Leopold M'Clintock who actually found what had happened. Certainly she was the driving force behind Franklin at every move, a far stronger woman than he was a man.

Aurora: Robert Peary is recognized as the first man to reach the geographic North Pole. What of the claim of Matthew Henson that he and his native companion were indeed the first to reach Camp Jessup?

Berton: Well, they all reached it. I mean Peary and Henson were together, but Henson was black, and so he never got any credit. But he got just as far as Peary did. Peary's argument was that he planned the expedition, that Henson couldn't have done it on his own, that he was there as kind of a helper, and that the man who really got to the North or close to it was the man who had spent most of his life trying to get there .That was his point of view, and I think there is something in that.

Aurora: You've described Robert Peary as one of the most single-minded and obsessed of Arctic explorers. Could you explain why?

Berton: He was not a very nice guy. Obsessed people aren't. He was very ambitious, but it was not so much ambition for fame as for fame as a means to fortune. It was the money he was after, and he had all sorts of schemes for making it.

Aurora: Did Peary fake his triumph at the North Pole?

Berton: The Navigation Foundation and the National Geographic Society have used new techniques for establishing where Peary was by examining the shadows of the photographs. The evidence up until late 1989suggested that Peary faked it. He was quite capable of faking it, having faked other things. The speeds that he travelled at were almost impossible to believe. So the evidence is very heavy against him not getting there, but I have to accept the results of what an independent group [the Navigation Foundation] spent a year investigating. Scientists have said that Peary, if he didn't get to the Pole, got very close to it. Some critics still insist that that evidence isn't very strong. The photographic evidence is very strong, although I don't understand the mathematical techniques they use to determine how the shadows work.

Aurora: Raold Amundsen was one of the long line of Scandinavian explorers and the first to successfully navigate the Northwest Passage in 1903 to 1905. He followed a route similar to that of the ill-fated Franklin expedition. Why did he succeed where Franklin failed?

Berton:First, Franklin didn't know that King William Island was an island. If he had known that, he could have gone around the back along the eastern coast and escaped the ice. This is what Amundsen did. Franklin might have made it through if he'd known that, but the maps of the day showed King William Island as a Peninsula.

Amundsen also had a ship that was specially constructed to do this job, while Franklin had very big, unwieldy bomb vessels. Amundsen completed the voyage with about six men. Franklin had over two hundred. Franklin had to feed them, look after them, and everything else. The Navy's expeditions to the Arctic were all overstaffed and overproduced. The only way to get through these difficult passages was with a small boat and a few guys. Amundsen did that.

Amundsen's purpose was not just to find the Northwest Passage, although that was the glamorous part. It was to take scientific measurements of the North Magnetic Pole. In fact, he spent the best part of two years, which he could have used to go through the passage, sitting on King William Island performing various scientific experiments. He was quite a different kind of explorer than Franklin or Peary or most of the others. Also Amundsen was a Scandinavian. His group had furs and proper food, and they lived like the natives. They didn't bring their environment with them as the British did. Also, there was no class-consciousness among the crew. They all pitched in and worked. There were no officers separated from men as in the British Navy. They were a very close-knit group of comrades, which was good for morale.

Aurora: Amundsen and his crew busied themselves with scientific experiments and visits with natives in the vicinity. Did this account for the loss of the Franklin expedition and the success of Amundsen's voyage?

Berton: One of the worst things that could happen in the North is to die of boredom. Look, you're sitting on a ship that's locked into the ice, it's had the mast taken down, it's covered with several feet of insulating snow, and you can't move more than a hundred yards from ship because there are no shadows to indicate where you are. You could get lost instantly in that Arctic wilderness, so you sit in these tiny ships with men and hammocks and bunks all crammed together, going absolutely mad from lack of something to do.

The early explorers tried their best: Edward Parry, the British seaman who began his Arctic explorations shortly after the Napoleonic Wars, brought theatrical costumes to put on plays, he brought a printing press to put out a magazine, and he had a hand organ to provide music. But even then, people tended to go goofy. Amundsen and his people worked continuously. There were only a few of them, and they kept busy completing scientific experiments.

Aurora: The contributions of the native peoples who assisted the various explorers such as Robert Peary and the eccentric American explorer Charles Hall have been ignored by the explorers, by the authorities, by the contemporary press, and finally by historians. How do you see the role of the native peoples within these various expeditions?

Berton: Very few of the explorations would have been successful without the assistance of the Inuit. The British, American, and Scandinavian explorers needed native hunters to provide them with food. They needed native women to keep them warm and sexually happy. They needed native peoples for companionship and to relieve the boredom. They needed natives to teach them about what to wear, how to eat, how to travel, and they also needed them as map makers. The Inuit are remarkable map makers. They could sit down with a pencil and piece of paper and accurately draw all the inlets on a piece of coast line. They had the kind of a mind that could understand the shape and the contours of the land. Time and time again, they saved explorers a lot of time, perhaps lives, by showing which way these guys should go.

Aurora: You are very critical of the evangelism of the Arctic explorers who, as Christians and in spite of their admiration for the aboriginal's adaptation to the northern environment, wanted missionaries to go out and save these people.

Berton: This was standard in the Victorian Age. They wanted to Christianize everybody. They thought that these people were very unhappy living without, as they put it, the benefits of civilization. What they didn't understand was that these people, over tens of thousands of years, had evolved a civilization and culture which was quite rich and which suited them because it suited the environment in which they lived. But every explorer, except for people like Amundsen and Peary who didn't believe in evangelism, said oh, if only we could get missionaries and some people to teach them really how to live, then they'd be much happier.

Both the government and the churches were blind and arrogant, and placed their own interests ahead of those of the Inuit. I have not much use for missionaries. I think they should stay home and run their own religion in their own country and not try to spread to other people who don't need and don't want it. I was born and raised in the North, and I have not seen that the missionaries have been of any value at all. They have taken away the language and the culture of the people and tried to turn them into white Canadians. It's agonizingly brutal!

Aurora: Your narrative demonstrates the superiority of native methods of living and travel, over the sledging and other methods of British and American explorations. Why have historians ignored native roles in Arctic exploration?

Berton: Well, white historians, by and large, have had the same attitude towards the natives that the explorers held–that the Inuit were a degenerate breed of aborigines who couldn't possibly teach us anything. This was the pattern of nineteenth- and early twentieth- century thinking. It's only recently that historians have paid more attention to the natives.

Aurora: As a historian, how would you suggest historians attempt to overcome these omissions of the role of the aboriginal peoples?

Berton: Well, their oral history is pretty good. They haven't been contaminated by too much information. The most startling example of their oral history being correct is the oral history of Frobisher Bay, which went back I think 250 years between the voyages of Martin Frobisher and the arrival of Charles Hall who found that the natives could remember accurately how many ships, how many men, and how many voyages there had been to the Bay. Three ships had been lost since Frobisher's day, and the natives took Hall right to the spot where the coal that they had brought with them was still lying around in piles. I think it's important to get these stories down now, late as it is, before oral history from the native point of view becomes obsolete.

Aurora: What was the impetus behind the writing of The Arctic Grail?

Berton: I started out to do a series of profiles of explorers and soon realized it needed much more than that. I scrapped that idea and started the research again. I try to tell narrative history. That is, I start at the beginning and end up at the end. Most of the books that I've read on the Arctic don't do that. They are very confusing, especially when dealing with the Franklin period because they jump all over the place.

I wanted to reconstruct the Arctic exploration almost month by month, year by year, so that the thing made sense over a period of 90 years. Historians have been separating the Franklin Expedition from the earlier explorations of the Northwest Passage and the later explorations of the North Pole. Actually, it's all the same story. It should be a seamless story from start to finish because you can't separate one from the other.

Aurora: What are you currently working on?

Berton: I'm just finishing up the last chapter of a narrative history of the Depression. The story starts in 1929 and goes to World War II, the period that we usually call the Depression. It deals with the whole of Canada on a year by year basis so that you can follow the story. There is a fair amount of analysis too.

We were very badly served by our politicians and businessmen during that period. Although I use much oral history when narrating the role of aboriginal peoples in the War of 1812 and in the explorations of the Arctic, I am a great believer in going back to original documents, to reading diaries, letters, and newspaper accounts written at the time. I think these documents provide the strongest underpinnings for a book. The oral history provides the raisins in the cake.

The Mysterious North: Encounters with the Canadian Frontier,1947-1954, 1956 and revised 1989.

Klondike: the Last Great Gold Rush, 1958

The Secret World of Og, 1961

The Comfortable Pew, 1965

The Cool, Crazy, Committed World of the Sixties, 1966

The National Dream, 1970

The Last Spike, 1971

The Dionne Years: A Thirties Melodrama 1977

Why We Act Like Canadians, 1982

The Klondike Quest, 1983

The Arctic Grail, 1988

The Great Depression, 1990

Picture Book of Niagara Falls, 1993

My Times: Living with History, 1949-1995, 1995

1967: The Last Good Year, 1997

Welcome to the Twenty-First Century, 1999

© Copyright 2000 AURORA

Citation Format

Berton, Pierre. (1990). Raold Amundsen: Native Peoples and Arctic Exploration. Aurora Online: