The Last of the Crazy People, 1967.

The Butterfly Plague, 1969.

The Wars, 1977.

Famous Last Words, 1981.

Not Wanted on the Voyage, 1986.

The Telling of Lies, 1986.

Headhunter, 1993.

The Piano Man's Daughter, 1995.

Pilgrim, 1999.

Spadework, 2001.

Apocalypse Now

We can never forget. We must be aware that the apocalypse is not only imminent, it is happening now. The bomb is not the only threat hanging over the human race. It includes our move towards the bomb. The dropping of the bomb has begun.

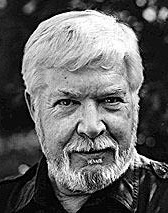

Timothy Findley was generous and patient with interviewers. He listened carefully, and responded thoughtfully. He arrived early and paid for his own breakfast, even when suffering through a bad cold on a dark morning of an Edmonton winter. He was a man of conviction - his novels and plays all warn against the proclivity of the human race to self-destructiveness. But he also celebrated creativity and kindness. In the worst of all possible worlds, there is still some hope of salvation.

My first conversation with Timothy Findley was about his early novel, The Wars, which I believe in many respects is his best work. My second interview was about The Telling of Lies, the first of several "metaphysical mysteries" in which the search for a murderer is an investigation of the human heart and mind. Findley returned to the scene of the crime in his last novel, Spadework, set in Stratford, Ontario, where he had worked as a young actor with the Shakespeare Festival, and where his play, Elizabeth Rex, premiered in 2000. Findley won the Governor General's Award for this play, and for The Wars. But as the many testimonials of writers, actors, and friends made very clear when he died, "Tiff" was also a mentor and an inspiration to many writers in Canada. And he was also a collector of cats, when he lived on a farm in southern Ontario. In Not Wanted on the Voyage, Mottyl, the blind cat, is Findley's seer. The biblical flood he revisits in this novel will be only the first of many human catastrophes.

The Wars by Timothy Findley is a searing indictment of man's capacity to destroy the living creatures of his planet, to turn the basic elements of life-earth, air, fire, and water-into the engines of death. The book's graphic images of the holocaust of World War I burn into the imagination. All of Findley's works-short stories, plays, novels-confront uncompromisingly man's terrible capacity for self-destruction. His novel, Not Wanted on the Voyage, which was nominated for a Governor General's Award, uses the biblical myth of the flood as an image of an inevitable cataclysmic Third World War. Many of Findley's works are set in times of war, and see human nature in terms of confrontation and conflict. I asked him to talk about how he perceives the role of the author in a society rapidly escalating towards global conflict.

Aurora: What intrigued me about The Wars and Famous Last Words was that you used war as the backdrop, as the social and environmental setting for your characters. When I recently read Not Wanted on the Voyage, it seemed that you were extending that into a Third World War scenario. Although the story is cast far back in time, you really talk more about the possibility of another "flood" or the inevitability of it happening again. Is that the way you see the book?

Findley: Indeed. I have to be careful when I am writing, not to fall into the trap of saying, "This is what I'm saying." I illustrate what I want to say through people. The illustration asks, "Where does this come from?" And the book casts the question into the future. A careful reading would reveal that it passes through all of time.

Aurora: Yes, you create characters in terms of basic human impulses, kinds of behaviour, and ways of relating to others and to the world. It seems to me you do a similar thing to the historical characters in your other novels.

Findley: What I hope to do is to give a balance in the characters. There comes a moment when I think a character is entirely negative and what happens to this person is negative. I've got to find some positive aspect so that he remains human. Disasters don't come from monsters or insane people. To believe so would be to provide ourselves with the wonderful excuse that monsters like Hitler create these situations, and therefore we can renege on our own responsibility for creating the atmosphere in which such events happen.

Aurora: The theme of individual responsibility recurs in all your works. To some extent we're all potential monsters and can actually become so under certain circumstances, especially circumstances such as war. Certainly, this is the case during the "flood" in Not Wanted on the Voyage, when at the end, Noah's wife is actually wishing the rain would continue and the flood would continue so that the whole pattern of repression and cruelty would not start all over again. Your novels leave us with the feeling that inevitably, even if given another chance, people will do the same things all over again.

Findley: I'm afraid I do believe that. I believe it out of desperation. I don't believe it willingly, and I don't believe it with a kind of sigh: "Well here we go again." We seek hope and live in hope. At some point you've got to say that man hasn't changed and is not going to. If Noah's wife and her cat Mottyl were left at the end saying "Hallelujah," then the reader would conclude that we can survive, and everything will be just fine. I would have reneged on what the whole book was about. There must be awareness that there can be change. That's the reason I chose World War I or huge political upheavals. Such events allow me to portray people, society, and the values that make people believe what they believe and society function the way it does. As illustration for what you say about the human condition, these events are wonderful. I hate to say "wonderful," but it's quite true.

Aurora: I'm struck by the use of violent deaths, torture, terrible anguish, and suffering. Is this a way of bringing readers to the point of feeling in jeopardy, where they have to make choices?

Findley: That is really a question of how easily we forget and how we want to forget. We'd rather not think about football stadiums in Chile with people being herded inside. Why didn't we do something about Chili? Why did we behave in this appalling manner? We must be aware that the apocalypse is not only imminent, it is happening now. The bomb is not the only threat hanging over the human race. It includes our move towards the bomb. The dropping of the bomb has begun. It is manifest in everything from the Quebecer who said, "It wasn't our fault that 10,000 or 100,000 caribou got drowned," right through to David Suzuki saying on television that we've been caught with a sudden emergence of a famine in Africa. We haven't been caught by any sudden emergence.

Aurora: You graphically portray the stupidity, the futility, and the horror of the terrible losses of the First World War, and I sensed you were saying that we must never be allowed to forget the Jewish holocaust and other atrocities that went on in the Second World War. Is one of your functions as a writer to remind people of historical facts-that they must never be allowed to be reinterpreted, glossed over, consigned to oblivion?

Findley: Dead on, except I would change one word. It isn't that I see that as my role; it's that I have to accept that as my role. When I sit down at the typewriter and think about what's going to come, I think, "Oh, no, not this again." It is not good enough to turn away, because I don't want to confront history on the page again. It's something I must accept. I am personally appalled and confused when I see writers in our time turn towards what I have to call the "Right", which is a particular kind of self-protection through the gaining of power.

Aurora: Fascist writers, in other words.

Findley: Yes.

Aurora: In Famous Last Words, the writer with integrity is the young Spanish poet, who wrote in the sky with the smoke of his plane a warning to the people below.

Findley: Yes indeed, and he was based on a very real Italian poet who died in that way over Rome. He's one of my heroes. He had to learn how to fly in order to make his flight. He purchased an airplane and dropped leaflets over Rome. He came from a very wealthy publishing family in Italy and believed that Mussolini had brought the end of the world to his country. He felt it was like dropping bread on a starving city, because of the censorship in the papers and so on, to remind the people that everything was right wing. He knew his airplane didn't have enough fuel to get home to safety in the South of France. He had to parachute and knew he would perish. This was a great gesture by a writer. He was a truly wonderful man.

Aurora: In your books there is also a search for a hero. In The Wars, the protagonist is seen as a hero because he cares for human and animal life, and then dies because of that conviction.

Findley: He died for life. The thing that moved me in writing that book was that Robert Ross believed above all else in life. If you couldn't save people, but you could save the horses, you were, in fact, saving life. You were making a statement about life. The whole point of life is that life itself is the embodiment of hope. That is why the birth of a child is always so moving.

Aurora: In The Wars, you write of Robert Ross: "He did the thing that no one else would ever dare to think of doing. And that to me is as good a definition of hero as you'll get. Even when the thing that's done is something of which you disapprove." How does this square with the epigram for the book, taken from von Clauswitz: "In such dangerous things as war the errors which proceed from a spirit of benevolence are the worst?"

Findley: I've placed that there in an ironic sense because von Clauswitz's writing is a well-articulated poem on the wonders of war. He is the one who made the statement about war being the ultimate means of solving political problems. He speaks of the beauties of human beings within a war context, and the epigram is one of the more astonishing things that he said. In other words, he's saying, "You can bring about disaster by caring."

Aurora: And you believe the exact opposite, that the only way we can prevent disaster or prevent another war is by loving life.

Findley: I think it's quite obvious. You had a perfect example of von Clauswitz in Mr. Reagan who said we must give our backing to these "freedom fighters," when in effect if he believed in human life, in all the human things he says he believes in, he should have done something that was humanitarian. Since he became President, his answer to Nicaragua were not compassion for the people, the human condition, or the condition under which they lived in that country, but to say, "We must get these bloody communists." He created that regime. He created an enemy by forcing them to take stances against his war-like stance because he accepted that war was the only way to solve that problem.

Aurora: You also comment on political leaders in The Wars, and it's an excellent perception that leaders are ordinary people. They are not monsters and not mad, although there are degrees of madness in some of them. You say their passions are as ordinary as any passions that you or I experience. You touch on this in your short story "War." The little boy turns on his father who has intentions of going off to war and has forgotten to tell his son, or hasn't yet had the chance to tell him. The boy turns into a little monster himself, waging war against his father. Basic human passions have been aroused, whether in a little boy, or in a Reagan. In a war situation, such leaders touch off a communal monstrosity appealing to the basest of human instincts to get a whole country behind them.

Findley: Absolutely. It's so easy to do that; it's harder to do the other. I'm sure that Mr. Reagan and Mr. Mulroney with him were going on the basis of a distorted memory of what the 1930s was about, and the answer to that situation was war.

Aurora: You also suggest in The Wars that people are capable of any atrocity. If they can imagine it, then they can do it-the flame-throwers, for example.

Findley: That was an instance of someone asking, "What is the most insidious, terrifying thing you can do?" Nothing is more frightening than fire, and so they created the flame-thrower. That thinking has continued to this day with the creation of new weapons as a means of creating terror. To terrorize people into submission.

Aurora: That really is frightening when you consider that we have already not only imagined, but invented and possess a weapon that can kill us all. It seems almost inevitable, given these terms, given history, that it's going to be used again.

Findley: I'm afraid so.

Aurora: At the end of The Wars you ask, "Can men ever be forgiven such atrocities, can they be forgiven the terrible things that they do to each other?" You leave that as an open-ended question. Do you intend the answer to be no, that we must never forgive these things?

Findley: There are ways of forgiving that embrace hope. Not mere gestures, ill-timed and ill-conceived, that pass for forgiveness. The first step towards forgiveness is the recognition that the impulse to do what was done is human and therefore resides somewhere in each of us. You know, the anger and the fury and the rage. When I finished Not Wanted on the Voyage, I sat in my kitchen feeling very bleak, but basically I felt rage. Forgiveness begins with the recognition that the terrible things we do to one another come from somewhere that is human. Those who have the capacity and do not halt these terrible things are in dire jeopardy of not being able to receive forgiveness.

Aurora: That's what you call intellectual cowardice.

Findley: Exactly. They've reneged on saying no.

Aurora: When they have the means to say no, that is, the intelligence, the talent, the imagination, and they don't use these means, they debase themselves, they betray themselves by not using what they have for the right reasons, for the right causes.

Findley: Betraying themselves, they betray everyone else.

Aurora: And that's Hugh Selwyn Mauberley from Famous Last Words in a nutshell.

Findley: Mauberley recognized his betrayal. He recognized it too late, but he did ultimately confront it in the very last thing he wrote: "Thus, whatever rose towards that light is left to sink unnamed: a shape that passes slowly through a dream. Waking, all we remember is the awesome presence, while a shadow lying dormant in the twilight whispers from the other side of reason; I am here. I wait." Imagine all the things within us that want to emerge and want to have life that we suppress because we are afraid that not to go with society, not to march when we are told to march is going to put us in jeopardy. We must be willing to be in that kind of jeopardy instead of the jeopardy that, ultimately, is worse-the jeopardy brought about by blind obedience.

Aurora: So in your novels, you keep alive the images of men who have the right kinds of instincts and fears. You believe that the writer should be politically engaged more than preoccupied with literary and aesthetic values.

Findley: He has to be both. I don't think that a writer can be effective as a mere propagandist. It would produce appallingly bad writing. The writer has to be aware that he is an artist, and perhaps the artist has to dedicate himself to the best of what he perceives, and that inevitably involves choices.

Aurora: To return to the use of war in your works, you see war as a literary device, as well as a very real historical fact that we must never be allowed to forget. You use war as an image of the worst that can be within man. I think you say in Famous Last Words that it's a place where we've been exiled from our better dreams.

Findley: That says it best.

Timothy Findley's novel, The Telling of Lies, is subtitled "A Mystery," and like the best works of that form, it does immediately involve the reader in the complex solution of a murder. But there are many more mysteries in The Telling of Lies than the simple one of "who done it?" The implication is that all the characters "done it," that all are accountable, because all were witnesses to the crime. And everyone tells lies to protect themselves from any painful involvement with reality. Even the protagonist, Vanessa Van Home, finds it necessary to lie in her resolute search for the truth. As are all of Findley's works, The Telling of Lies is a comment on political lying and duplicity or "misinformation," an indictment of social and political corruption, ambition and greed, and a warning of the cataclysmic consequence of such corruption. As Vanessa learns, "the bomb has fallen down on all of us, and it is over, now. The War. Forever." "Someone sold us out - but only when we ceased to pay attention." The hotel on a beach in Maine, where most of the action takes place, is an image of our society, "a ship of fools," the Titanic just before collision with the iceberg. Although it holds within itself the rich history of the lives of several generations of American and Canadian guests, it is slated for demolition.

Timothy Findley toured across Canada for two and a half months to get people to pay attention to this imminent demolition. His readings and interviews were ways of provoking curiosity, stimulating an articulation of the feelings of frustration and helplessness which repress active involvement. Such public exposure is now very much a writer's responsibility. He, too, is accountable for his words. The hardest aspect of the tour for Findley was being away from home for such a long time, and not being able to write, just when he was coming up in his energies after the "postpartum blues" the writer experiences after seeing his last creation through the final edit, the galleys, the production process. In fact, during the tour, he literally started writing in his head, producing the lead sentence to a story, for example, but he did not have the time or opportunity to write it down. And once the process starts, the great danger is that it will continue all the way through. He had to learn to hold it there, and keep everything behind the first few sentences, praying he wouldn't lose them. If he let them out, and couldn't develop them because he was traveling and there was no time, then he would have started a process that came to nothing.

But, for Timothy Findley, there was no question about the value of touring: only three weeks into his tour after the publication of Not Wanted on the Voyage, he discovered in Calgary that the book was already on the best-seller list. And that also happened with The Telling Lies, which topped Maclean's fiction ratings while he was in the Maritimes. Touring raises the consciousness of the readers and brings them into contact with the book. Meeting the audience is also wonderfully stimulating - especially the students at universities who were studying Findley's works. As a writer gets older, discussion with young people becomes very important, so that he does not get locked into his own generation. But any audience can be challenging and unpredictable. Their questions may embrace the same territory, but because the milieu is different, the individuals are different and their reasons for asking are different. The standard questions are never the same; consequently, Findley's answers could have a kind of variation. On top of the common context, are the particulars: for example, in some places feminism had not made the same strides that it had in others, so that the feminist content of his work, which is very noticeable in Not Wanted on the Voyage, raised more questions in Newfoundland, for instance, than it did in Ontario.

Findley chose the passages for his forty-five minute readings very carefully - for length, for balance, for entertainment value, for thematic importance. For his appearance at Greenwoods Books in Edmonton, he chose an amusing passage from The Telling of Lies -- Vanessa's encounter with a nude Canadian diplomat on the beach -- and a disturbing passage from The Butterfly Plague in which Ruth encounters a desperate Jew begging for money in the streets of Paris to get his parents out of Nazi Germany. In universities, he read from something the students may be studying, the shooting of the horse in the hold of the troop ship in The Wars, for example. For these readings, Findley appreciated his training and experience as an actor, because in the theatre he learned how to muster his energies at the end of the day for a public performance, how to breathe and project properly.

There were, inevitably, the hostile audiences, people who could not bear what he has done with God in Not Wanted on the Voyage, people who misunderstood what he was doing. One reaction really startled him -- when he was accused of ridiculing women and the elderly in The Telling of Lies, an accusation which indicated a complete misreading of the novel. Or he got "wonderfully weird" criticisms: "You have not concentrated in your novels, as you should, Mr. Findley, on the problems of homosexuals. How dare you write about other problems, when that is the central problem." His response was that there was still the small matter of the bomb to be dealt with.

Public readings were for Findley another manifestation of the human need for articulation, as were private readings-the discovery of the right way to express, and therefore realize the most profound feelings and ideas. We all need someone to articulate what we cannot when we are trying to focus something. During the question period following a reading, when a conversation is going, what most often comes out is a common recognition. The audience appreciates the opportunity to say collectively what as individuals they have not been able to articulate. If there are more and more people sharing a recognition of political "misinformation" or doublethink, for example, who then resolve not to tolerate these things, one day they will vote the perpetrators out of power. That is the collective possibility. We really can change things.

When asked to analyse his own work by readers who wanted to test their own interpretations against his, Findley willingly did so, although he also respected the inexplicable "givens" in writing, the right words which come of their own volition --Vanessa Van Home's ambiguous insights which conclude The Telling of Lies, for example:

Yes. It is time the icebergs came.These are the kinds of experiences in writing which are wonderful, because they come from the integrity of the work itself. Quite often there is a lot in the work that the author does not realize he has put there that makes a lot of sense-that gets there on its own. The formal analysis he leaves to the academics. That's what criticism is-the academic approach to what is there which helps to produce the direction of the novel, where it can do its work in ways that people may not have suspected.

Even the choice of protagonists in the novels is not a conscious one. These people simply present themselves, although Findley was very wary of those who are echoes of characters in his other works. Individuals whom he had actually met may also have provided a certain tone of speaking and living which inspired a characterization, the prototype for Vanessa Van Home, for example, whom Findley met at a favorite hotel in Maine. This elderly lady had always dealt honestly with herself and with others, so that now she was at the end of her life, she was still looking forward to whatever came next rather than dealing with things in the past.

Timothy Findley's protagonists are usually women. His only successful "hero," that is, a man who has honestly come to terms with his life and his death, is Robert Ross in The Wars. Other male characters have had positive qualities and strengths, but Findley felt that men are defeated by weaknesses that we do hot acknowledge enough, the weakness of male reliance on violence, for example. The men in his works are confronted suddenly with the realization that what they thought was strength is in reality a weakness, and they don't adjust at all well. And women have certain physical strengths which have not been acknowledged by men, but which they have always known they had. Another thing which is not successfully dealt with by men in their writing, although it has been dealt with by women, is the fear which men have of women. They are afraid of what women are about, which means they don't understand what they are about themselves. Nor can women fully understand what it is to be a male in a sexual sense, the surge of sexuality which for men is an immense thing to contend with. These incomprehensible differences are, however, what constitute the attraction between men and women, the mystery. The people who are the most successfully "in love" and who go on loving one another are those who honour the mystery of the other and are intrigued by the endless exploration of what that means. Findley's novels are all engaged in just this kind of exploration.

Timothy Findley died in Provence, France, on June 20, 2002 at the age of

71.

Novels by Timothy Findley

The Last of

the Crazy People, 1967.

The Butterfly Plague, 1969.

The Wars, 1977.

Famous Last Words, 1981.

Not Wanted on the Voyage, 1986.

The Telling

of Lies, 1986.

Headhunter, 1993.

The Piano Man's Daughter, 1995.

Pilgrim, 1999.

Spadework, 2001.

Novella

You Went Away, 1996.

Short Stories

Dinner Along the Amazon, 1984.

Stones, 1988.

Plays

Can You See Me Yet? 1977.

The Stillborn Lover, 1993.

Elizabeth Rex, 2000.

The Trials of Ezra Pound, 2001.

Shadows, 2002.

Non-Fiction

Inside Memory: Pages from a Writer's Workbook,

1990.

Other literary works include collaborative and edited works, scripts for television, radio, and film. Awards and honours include four Honorary Doctor of Letters, Governor General's Award for Fiction, the Edgar Award, the Chalmers Award, and the Canadian Author's Association Award (three times). He was an Officer of the Order of Canada and Chevalier de l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres in France. He helped found, and served as chairperson for the Writer's Union of Canada.

Dr. Nothof is a professor of English literature at Athabasca University.

Order from National Film Board of Canada Timothy Findley: Anatomy of a Writer

Updated May 2018

Aurora Online

Citation Format

Nothof, Anne(2002). Apocalypse Now Timothy Findley. Aurora Online: